Cooking up a storm with Bill Twaler of the International Culinary Institute of Myrtle Beach

According to the Myrtle Beach Area Hospitality Association, there are approximately 1,800 restaurants along the Grand Strand. Here you’ll find seaside resorts, fine dining steak and seafood houses, decades-old venerable institutions and brand new eateries with sophisticated urban cuisine. These establishments all have one thing in common: a very real need for trained chefs.

Bill Twaler of the International Culinary Institute of Myrtle Beach (ICI) is one of the many chef-educators charged with the training of these future chefs. He’s worked at the ICI since August 2017. A former restaurateur and culinary arts teacher at Wando High School in Charleston, Twaler now works to ensure this next generation of ICI graduates knows its blanching from its braising, simmering from poaching, and just how to render its roux and coddle its cocottes.

The ICI reimagined itself as a part of the Horry-Georgetown Technical Institute’s family of schools in 2016 as a standalone, state of the art, $15 million culinary arts education center on The Market Common campus in Myrtle Beach.

In my ongoing exploration of the Grand Strand’s most interesting jobs, I wanted to see just how tomorrow’s chefs are trained and what the rigors of a typical classroom day might be.

6:45 a.m.

I started my day shadowing 48-year-old Chef Twaler in the naturally lit, pristine hallways of the ICI at 6:45 a.m., where, still bleary-eyed, I was treated to fresh coffee made from locally roasted and sourced coffee beans. The locavore (locally sourced) movement is big here. The coffee is sold alongside student-made pastries at Layers, a little shop staffed by Twaler’s wife of 17 years, Lia Sanders, who is bakery manager.

Equally bleary-eyed students were arriving, too. Most are in their late teens and 20s, a few a little older, along with a handful of middle-aged men and women. Everyone, including Chef Twaler, a self-professed night owl, was eager to get on with the day.

The sleek, glass-enclosed “aquariums” that are the ICI’s classrooms are outfitted with the best kitchen equipment and closed circuit television-ready technologies available, all designed to meet head-on the modern challenges of teaching both cutting edge and very old classical cooking techniques. “Everything in this class, today anyway, is classical French cooking,” said Twaler, who looks like he’s stepped off the pages of Chef’s Illustrated. A friendly man with rosy cheeks and a quick smile, Twaler is equal parts funny, serious, sarcastic and everything you’d expect from an experienced chef and educator. He’s fun, but he’s all about the business of cooking, and his students treat him with the respect his impressive resume and years of classroom teaching deserve.

“This will be one of the toughest days of the semester,” Twaler tells me, “because today I’m going to teach the tourne (tore-nay), which is the hardest knife cut known to man.” The tourne is a seven-sided football shaped classic cut usually done with potatoes and other vegetables. Additionally, the students are each going to break down a raw chicken, prepare it for a grade, then prep for the Family Meal Day, a luncheon of student-invited guests.

7:15 a.m.

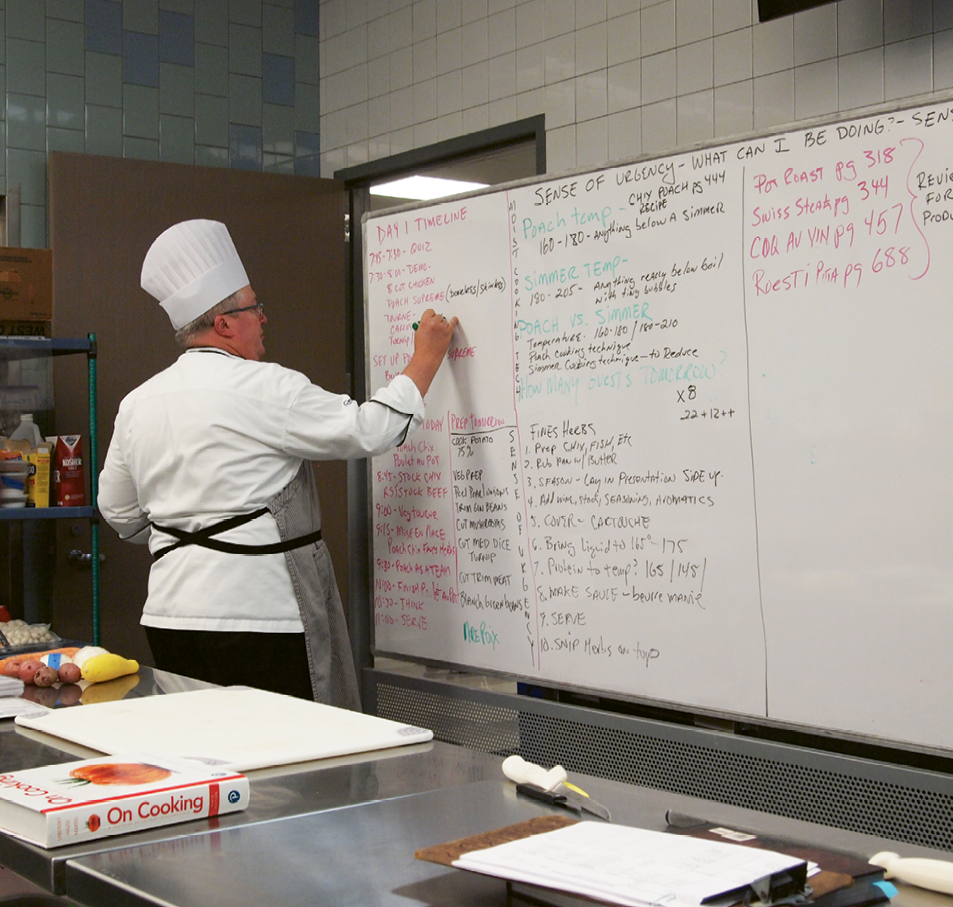

As the students, aged 17 to 48, shuffle in, I stand to the side while Chef Twaler goes over the day’s timeline written on a giant dry-erase board. There’s a lot to do before noon and it starts with the tourne demo. The 11 students—two were absent that day—first gather to watch Twaler, then assemble into small teams. They’re all decked out in stark chef’s whites, the uniform of the school, and black hats called skullcaps. For 30 minutes they struggle and succeed, to varying degrees, with the tourne lesson, all part of Chef Twaler’s class, Classical Foundations of Cooking. Twaler constantly moves around the classroom to critique, grade and instruct. His tall hat, a snow-white chef’s toque, acts as a moving beacon, making him easy to find.

Xokxay Phonsina is an international student from Laos. The 17-year-old hopes to join his family’s restaurant business armed with new skills from his ICI two-year associate degree in the culinary arts.

The students line up for inspection as Chef Twaler reviews their homework; individual recipe cards, equipment lists and timelines. The process is quick and he grades each student with his ready pencil and clipboard. “Remember, we talked about this,” he says to the entire group, his tone stern. “This is important.” He implies more than once that failing in the classroom spells real trouble in the practical world of challenging restaurant kitchen management.

8:30 a.m.

“Don’t spend any more than 30 minutes on your tournes,” says Chef Twaler, his voice booming. “I want you to move on with your prep. Watch your time.” With tourne instruction wrapping up, students go to the giant walk-in cooler and each get a raw chicken. I tell Chef Twaler how jealous I am of the instruction his students are getting. “I’ve always fantasized about a Culinary Arts Degree,” I tell him. “We offer continuing ed classes on the weekends,” he says. “This Friday, I’m teaching knife skills and shrimp and grits. I work so damn much,” he laughs. He checks the oven where beef and veal bones are roasting, filling the classroom with an intoxicating, rich aroma. “This goes into the stock we’re making for tomorrow’s pot roast,” he says, sliding the large tray of bones back into an oversized commercial oven.

Twaler has an easy rapport with his students and with me, happy to share stories as they come to mind. “I spent three months as a safari chef in Africa for a family from Charleston a few years ago. That was fun.” When I asked about the most exotic game he prepared for them he repeated the question to the classroom. “Paul wants to know, what was the most exotic thing I cooked in Africa?” Without looking up, they all yell in unison, “Rat!” They’ve heard the story before. “The animal is called rock dassie,” explains the chef, “but it’s kind of rat-like. Tastes like rabbit. Delicious. As the story goes, if they brought it into my kitchen, I cooked it. They freaked out a little bit, but I told them it was at least ‘free-range, organic rat.’”

8:45 a.m.

Twaler takes his sharp boning knife and demonstrates how to dissemble, or “break down” a chicken; finding the joints, reducing the bird to its useable parts, explaining each step, finishing in a minute or two. The students spend the next 30 minutes on their chickens and it’s clear that it’s not as easy as he made it look. With their frustration evident he addresses them all with that unmistakable teacher voice. “Look, you guys have only done this once before. You’re here to learn. I’ve done literally thousands of chickens. When you’ve done thousands of chickens it will seem easy to you, too.”

9 a.m.

I notice lots of pots and pans as the students prepare to cook the chickens they’ve just broken down, but no lids. Instead they make a cartouche, a parchment paper origami makeshift lid. The unmistakable influence of French cuisine is everywhere, and especially evident in the French words used in Twaler’s class—cartouche, toque, tourne, mirepoix, sauté, sous vide, poulet au pot, mise en place and others.

9:40 a.m.

Always with an eye on the clock, Chef Twaler again uses his teacher voice to fire up his charges. “It’s 9:40!” he yells. “Always check your timelines. We don’t have an unlimited amount of time to play around here.” In many ways, his classroom operates under the same kind of pressure a restaurant’s kitchen would, and I guess that’s the point. Twaler and his wife owned and operated The Old Firehouse Restaurant in Hollywood, South Carolina (just south of Charleston) for 15 years.

The student teams are now cooking the chicken they’ve broken down. The first group is making poached poulet au pot, chicken in a broth with vegetables. Others plate up their poached chicken with fines herbes, served atop a creamy lime sauce. “Hey, chef! How’s this?” asks one young man, his nervous smile just hidden. Chef Twaler looks, tastes and nods his approval. It’s all the student needs.

Again, with clipboard in hand Twaler grades each team. The highest score possible, #5, means the student prepared a flavorful, savory, moist and juicy piece of chicken. This is a dish that no customer at any restaurant would send back.

10:20 a.m.

We all eat, family-style, standing right where the students have plated up their assignments, poking our forks in each other’s poulets. A few of Twaler’s chef-educator colleagues wander through and taste the day’s lessons, offering their own critiques.

The cleanup begins in earnest and all chip in to hand wash, dry and deliver pots, pans and silverware to a waiting Chef Twaler. He inspects each and every piece for the smallest morsel of missed food before stowing it all away in a supply closet.

11:30 a.m.

All of the classroom assignments have been completed and discussions about the big Family Day chores hashed out. Students begin to file out, done for the day. Twaler’s is only one of many active labs and classrooms that morning. One room down, some 25 students are making sausage, next to them a pastry class is in full swing, all while student-chefs ready the Fowler Dining Room for the day’s customers.

12:30 p.m.

Chef Twaler carves out enough office time for a considerable amount of administrative work. While he scans his emails, we discuss his background as a transplanted Iowan, his time working in the Northeast, and how, in the mid-1990s, he decided to pursue a culinary degree of his own to further his restaurant career. “I packed up, sight unseen and moved to Charleston, where it doesn’t snow and it’s warm.” In Charleston, he began a long trek toward many culinary degrees and certifications, two from Johnson & Wales University; a BS in Food Service Management and an AAS in Culinary Arts. In 2017, he completed his Master’s in Education at the University of Kansas.

“I started as a paycheck person,” he said, “hoping my degree would just get me better pay at whatever restaurant I was working at, but as I got into it more, my passions changed.”

His office wall is adorned with some of his many awards and certifications: Modernist Plating, Sous Vide Technique, BBQ Science, Charcuterie and Charcuterie Intensive. He traveled to Berlin, Germany, to compete in the world Culinary Olympics. He’s contributed to culinary textbooks and has coached culinary teams on to international championships. He was named South Carolina Hospitality Educator of the Year in 2016. In addition to teaching Classical Foundations of Cooking at the ICI, he also teaches Kitchen Fundamentals and Cuisine of the Americas, covering the regional cuisines of the U.S., South and Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean.

1 p.m.

With no real lunch break to speak of, Twaler, still seated at his desk, prepares for a Menu Planning class. A student, Deb Green, knocks on the door to discuss BBQ sauce in preparation for a Farmers Market. Twaler offers his advice and she moves on.

1:30 p.m.

Twaler hauls his laptop and PowerPoint presentation to the ICI’s indoor amphitheater, called the Demonstration Kitchen. It seats some 75 students, but this day a very small class of five sits to listen to the lecture and take notes.

2 p.m.

By 2 p.m. I am exhausted and I haven’t even done anything. Twaler keeps this kind of schedule up five days per week, often stopping for supplies on his way home and working nights and weekends grading and thinking about his class and students. “I don’t get to do the competition stuff as much as I used to,” he says, a bit mournfully, “but I still find a way to squeeze in a little. I really love it.”

Twaler tells me his typical day usually wraps up around 4:30, but that there’s “always something going on” that can cause his schedule to change. He leaves me with a bit of optimism about Myrtle Beach becoming a true food destination. “Charleston is 20 years ahead of Myrtle Beach in that respect,” he says, “but we can get there.”

3 p.m.

I leave Twaler to finish his menu planning class, my box of pastries from Layers securely tucked under one arm. It’s a long, rewarding, fascinating day filled with sweet and savory memories. As I pass countless fast food joints on my way home, I think about stopping at my favorite grocery store to find something good to cook. Or, with all the fantastic restaurants in town, I could let someone else do the cooking. After all, they’re the ones who really know what they’re doing.