S.C. Maritime Museum and CCU’s Joyner Institute work to broaden the narrative

No matter the topic, there’s always another side to the story, and history is particularly rich with those. Two area organizations are working to seek out and share stories of underrepresented voices within otherwise familiar South Carolina historical narratives. The process as well as the products of these endeavors promises fascinating insights to Georgetown County cultural perspectives often eclipsed from public view.

The South Carolina Maritime Museum in Georgetown and Coastal Carolina University’s Charles Joyner Institute for Gullah and African Diaspora Studies each received grants from the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation in 2021 for projects that will present a fresh dimension of area cultural history.

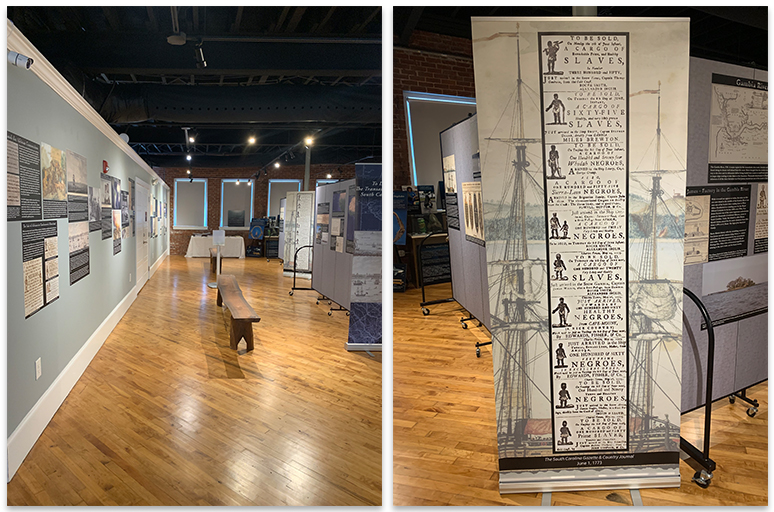

The South Carolina Maritime Museum has opened the first segment of Across Time and Many Waters: South Carolina’s Afro-Carolinian Maritime World, an exhibit that tells the story of Africans’ journey to America aboard slave ships, their contributions to the maritime industry, the post-Civil War transition of freedmen to maritime-related work in Georgetown County, and current perspectives on the legacy of the maritime trade.

The Joyner Institute, which is working through phase two of a three-phrase grant, is focusing on the Gullah Geechee Cultural Conservation project with the Plantersville Cultural Center and Hasty Point property in Georgetown County. Grant work involves collection of oral histories from community members in Plantersville and discussions about future cultural preservation. The Joyner Institute will hold a public conference and community day February 25-26, 2022, on the CCU campus and in downtown Conway, to showcase the importance of community-led and community-inclusive practices in preservation, cultural heritage, and tourism.

The Donnelley Foundation has a decades-long history of support for the South Carolina Lowcountry, specifically nine counties along the coast from Horry to Jasper. Founders Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley, of iconic Chicago printing company RR Donnelley, established their legacy of support for the South Carolina coast when they purchased land in the ACE basin and donated 10,000 acres to the South Carolina Department of National Resources as the Donnelley Wildlife Management Agency. With three areas of focus—land management, artistic vitality and regional collections—the foundation provides general operating support and project grants for dozens of organizations throughout the state totaling $2.5 million annually.

The S.C. Maritime Museum and Joyner Institute grants reflect the foundation’s new Broadening Narratives strategic plan, especially as it relates to the collections community.

“We’ve been particularly focused on museums, libraries, and cultural institutions trying to protect and preserve the stories of their communities,” says Kerri Forrest, director of the Lowcountry Programs at the Donnelley Foundation. “We wanted to take our focus off the objects and make it more about the story. When we encounter significant objects, we ask, ‘What is it about these materials that tells a different or undertold story about the communities we live in that’s important to a complete understanding of our community?’”

Justin McIntyre, curator and maritime historian at the South Carolina Maritime Museum, had planned to develop an exhibit on the Transatlantic Slave Trade in the near future, and the July 2021 Donnelley grant provided a perfect opportunity. With permanent exhibits featuring South Carolina shipwrecks, a history of South Carolina hurricanes and historic figure Robert Smalls, the South Carolina Maritime Museum was a perfect host for the grant and a project of this nature. The first segment of the exhibit, titled To Distant Shores: The Transatlantic Slave Trade to South Carolina, 1670-1808, opened in late 2021 and offers a sense of the magnitude and scope of the industry.

“The exhibit starts broad, showing the scale of the global slave trade, and narrows down to South Carolina,” says McIntyre. Some exhibits focus on African ports of embarkation, such as Cape Coast Castle, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and slave trading forts such as Bunce Island, located in Sierra Leone.

To Distant Shores serves as a foundation on which later exhibits will build. Segments to appear later in 2022 include one focusing on maritime roles that African Americans played during and after the slavery period.

“Many African Americans worked as patroons,” notes McIntyre. “‘Patroon’ means a boatman, but particularly the pilot or captain of a vessel—in Lowcountry South Carolina, that might be a canoe, periagua, plantation flat, usually a small boat or ship—or a senior boatman. Patroons were very skilled in the handling of a boat, knew how to navigate area waters and knew how to keep a crew of ‘junior’ boatmen in check.”

Susan Davis, vice president of the South Carolina Maritime Museum Board of Visitors, says the factual and contextual information in To Distant Shores is an important backdrop for future exhibit segments, which will also incorporate stories from current community members.

“Future displays will demonstrate how much our African American community contributed to Georgetown and to the economic value of Georgetown.”

The Plantersville Cultural Collective is part of the Gullah Geechee Digital Project, a larger Joyner Institute initiative that aims to showcase diversity and commonalities among South Carolina’s Gullah Geechee communities. The Gullah Geechee Digital Project encompasses St. Helena Island, Johns Island, Sandy Island, Murrells Inlet and Plantersville.

The first phase of the Plantersville Cultural Collective involved collecting oral histories from community members. The second phase involves connecting the dots, both within Plantersville and between it and other Gullah Geechee communities, says Alli Crandell, interim director of the Joyner Institute and director of CCU’s Athenaeum Press.

“We said, ‘Ok, here are the stories we’ve gained. How do they connect with one another and how do they connect with the wider region?’” recalls Crandell. “A lot of our work this phase is seeking feedback from community members that we interviewed, seeking feedback from the larger community and connecting this story to other initiatives: at Plantersville Cultural Center, they’re getting a new exhibit and Hasty Point Plantation is working on the final phase of defining what’s unique about Hasty Point within the region.”

Hasty Point Plantation, located in Plantersville, dates to the 1700s and includes a 200-plus-year-old rice barn. It was purchased by the Waccamaw National Wildlife Refuge in 2020 with assistance from Open Space Institute and Ducks Unlimited.

“We’ve been particularly focused on cultural institutions that are trying to protect and preserve the stories of their communities.” -Kerri Forrest, Donnelley Foundation

Crandell notes that Plantersville in particular has retained much of its original landscape and rural culture. It’s comprised of 13 historic plantations with much of the land still intact and features a pattern of villages originally established by the historic Gullah Geechee community. This stands in contrast to other Gullah Geechee communities in the lowcountry, where suburban neighborhoods and different phases of development have replaced that residential model.

“A lot of the historic houses are still there [at Hasty Point]; the pathways to the rice fields are still there,” says Crandell. “In contrast, on Sandy Island, none of the plantation houses are still there. It’s completely transformed—the freedman community determined the cultural landscape. Murrells Inlet is developed. The connection between Plantersville and the other communities is interesting—how Plantersville’s cultural landscape has survived, been preserved as a rural community. You can, in a way, travel through time and see how different choices and influences have changed how we define Gullah Geechee culture. The question is, with each of these communities, what can be saved? What will be saved? What is changing, and what’s the cost and the benefits of that change? Each of the communities presents different models of how and to what degree cultural heritage can be maintained.”

Zenobia Harper, Joyner Institute community outreach coordinator, has played a critical role in collecting community stories and considering how they should be implemented. A native of Georgetown and founder of the Gullah Preservation Society, Harper emphasized the importance of spending time within communities and building trust with residents.

“You need to spend a lot of time with people before you interview them if you want to get to a certain level of interview,” says Harper. “We’re trying to get to the meat, get down to the soul of the community. And it takes time to do that. We don’t want to do a disservice. You can get the statistics on how many roads, businesses, or plantations there are, but when you’re talking to the residents, you want to get to the soul of what that community is.”

The archived stories of Plantersville, in many forms, are on display at the Plantersville Cultural Center via an audio interactive tour.

Crandell notes that documenting the past is only part of the goal. Thinking about the future and connecting people from various communities with information and resources are perhaps even more important.

“We have discussions about the story, but also about entrepreneurship,” says Crandell. “How should we think about it? This tourist train is going to come. Development is coming. How do we help preserve this place? How can we offer resources from others who have done similar things around our nation to help inspire this space?”

Harper concurs, adding that in relation to other large-scale issues such as climate change, community residents are the very people who are aware of problems first, but whose knowledge is often overlooked by researchers.

“Often times, when you open a discussion up to the wider world, it is the indigenous people, the native people–those people who have their nose to the grindstone and work very closely with the earth and the water—who can tell you decades beforehand that there’s something happening,” notes Harper. “[Scientists and researchers] have to get used to everybody’s voice being at the table but not all speaking the same way.”

Creating an alliance, including through events such as CCU’s International Gullah Geechee and African Diaspora Conference, to be held Feb. 25-26, is essential to larger progress in cultural preservation.

“The most important thing is knowing [Plantersville] is not alone in that struggle,” says Crandell. With the public knowledge gained through these projects and the Donnelley Foundation’s Broadening Narratives initiatives, Grand Strand residents and visitors may gain a broader understanding of the wide array of voices in our communities.