Days at the downtown Kozy Korner Café

Once or twice a week, starting about 1951, as few as 100 and as many as 1,500 shaved-head, stiff-back Marines would invade the Kozy Korner Café, our little downtown restaurant.

They didn’t attack in tanks and Jeeps. They rolled in on long, shiny Greyhound buses.

Each bus carried a platoon of Marines, a driver and one shrill-voiced drill sergeant. The driver, the only civilian, was for driving. The drill sergeant was for screaming. You could hear the buses coming a mile down the road.

Growling like tanks with their air brakes groaning, belching black smoke, you could taste the diesel. They’d rumble into town, rattling windows, flattening cakes in the oven, and making babies cry and dogs bark.

The first bus would pull up to the front of the restaurant, and its shiny hydraulic door would hiss open. The yelling would start. Drill sergeants don’t ever talk. They bellow, bray, spit-scream. Seventy-five baby-faced Marines would spill out like gray mice dumped from a milk carton. Arms pumping, feet stomping, then an eerie stillness.

“TWOOO COL-LUMS, H-AAARM LENG, H-EYES FARONNN.”

With foreheads full of swollen blue veins pulsing power corpuscles and serial killer eyes, they bleated in a military abracadabra.

“HOWWWARD HARR.” Whatever that means, they would launch every spit-shined shoe in a forward direction. They’d file through the propped-open door into our restaurant. Right column split to the right, left column to the left. Haba-haba, they’d find a chair to stand beside. Then, quivering at rock-stiff attention, they’d await further instructions.

That’s how it’d start.

Then the second bus would pull up and do the same. Other buses would line up all down the block like silver dragons, idling in wait.

“SEEEEATS!” the jut-jawed drill sergeant would bellow.

Violent choreography. One long thunderclap of 150 Marines collapsing into aluminum booths and bentwood chairs, eyes front, hands in their lap, chins tucked back, ready to chow down. Three seconds of grayish, boiling movement, then absolute silence except for the background clatter of dishes and silverware.

Mom and Dad always turned over seating duties to the drill sergeants. More efficient, they said. Unlike other maître ’ds or hostesses who give a damn where you sit, drill sergeants are only interested in how quick your butt hits the seat.

None of this, “I’d like to dine by a window” or “Please don’t seat us next to the kitchen.” Definitely no “We prefer a booth,” “Can we get separate checks?” or “We’d like Vivian’s station.”

If one of those Marines malingered too slow or was ballsy enough to complain about his seat, chances are he’d be verbally and physically body slammed into the nearest chair. Something every restaurant man always dreams of doing to an obnoxious customer.

These young gyrenes, fresh and buff out of boot camp, were en route from Parris Island to Camp Lejeune. This meal would be their only stop along the way. They didn’t know it yet, but many of them were three months away from Korea, from fighting, freezing and dying on the Yalu River, Pork Chop Hill and Heartbreak Ridge. My parents won the right to serve these Marines by bidding successfully on a government contract. Successful because theirs was the only bid.

Making a Living

This was the ’50s. The “separate but equal” years.

No other restaurants bothered to bid because some of the Marines were off-white, some brown. Back in those days, the only non-whites allowed in restaurants were holding brooms, cooking or picking up to-go orders from the side door. Bet a dollar to doughnut the Kozy Korner was the first restaurant in the county to allow an African-American man to sit in the dining room and eat a meal.

Charlie Fitzgerald, black nightclub and motel owner, who had yet to hear, much less heed Sam Cooke’s lyrics, “I go to the movie and I go down, somebody keep tellin’ me…don’t hang around,” had been supping with us since the mid-1940s, as well as sending us black guests from his motel which was listed in the Green Book.

To my mom and dad, no big deal. They weren’t making history, they were making a living. All they saw was hungry folks in or out of uniform.

One hundred-fifty Marines at a time. That’s how many seats we could cram into the upstairs/downstairs dining rooms. Downstairs was The Hide-a-Way, a basement beer joint converted to military mess hall on Marine days.

The menu was simple. Bulk was more important than presentation. These jarheads could eat the rear end out of a rag doll. The meal, same for everyone, even drill sergeants, was:

One-pound ground-sirloin seasoned like a Greek keftethe (meatball)—diced onions, bell peppers, salt, oregano, mint, grated cheese, parsley—then smothered in a hearty mushroom sauce.

We called it a hamburger steak. It was more like a meatloaf football. Too big to grill, we oven-baked them. The “meatloaf football” was accompanied by parsley potatoes, green beans, creamy coleslaw, two cartons of milk, a glass of iced tea and all the rolls and butter they could eat. Dozen rolls per Marine? Nothing unusual. John Schiller, the stumpy Austrian baker who supplied the rolls, would call the restaurant every day for his order. “Hey Tony, how many Marines coming today?”

Dessert was two paper cups of Sealtest ice cream. One chocolate, one vanilla. Separate but equal dessert. $1.25 per Marine was our price.

Before Fast Food

In and out, 15 minutes flat. All of this before they invented fast food. Drill sergeants screaming them off the bus, barking them down the sidewalk, growling them into the restaurant, shoving and poking the ones who lingered, pounding on tables and bellowing, “Eat faster, jarheads!”

Slow chewer? Drill sergeant would slam your platter upside down, splatter food over our black Formica tabletop, order him to eat it. Marines always complied. You can see why we never had other customers in the restaurant on Semper Fi days.

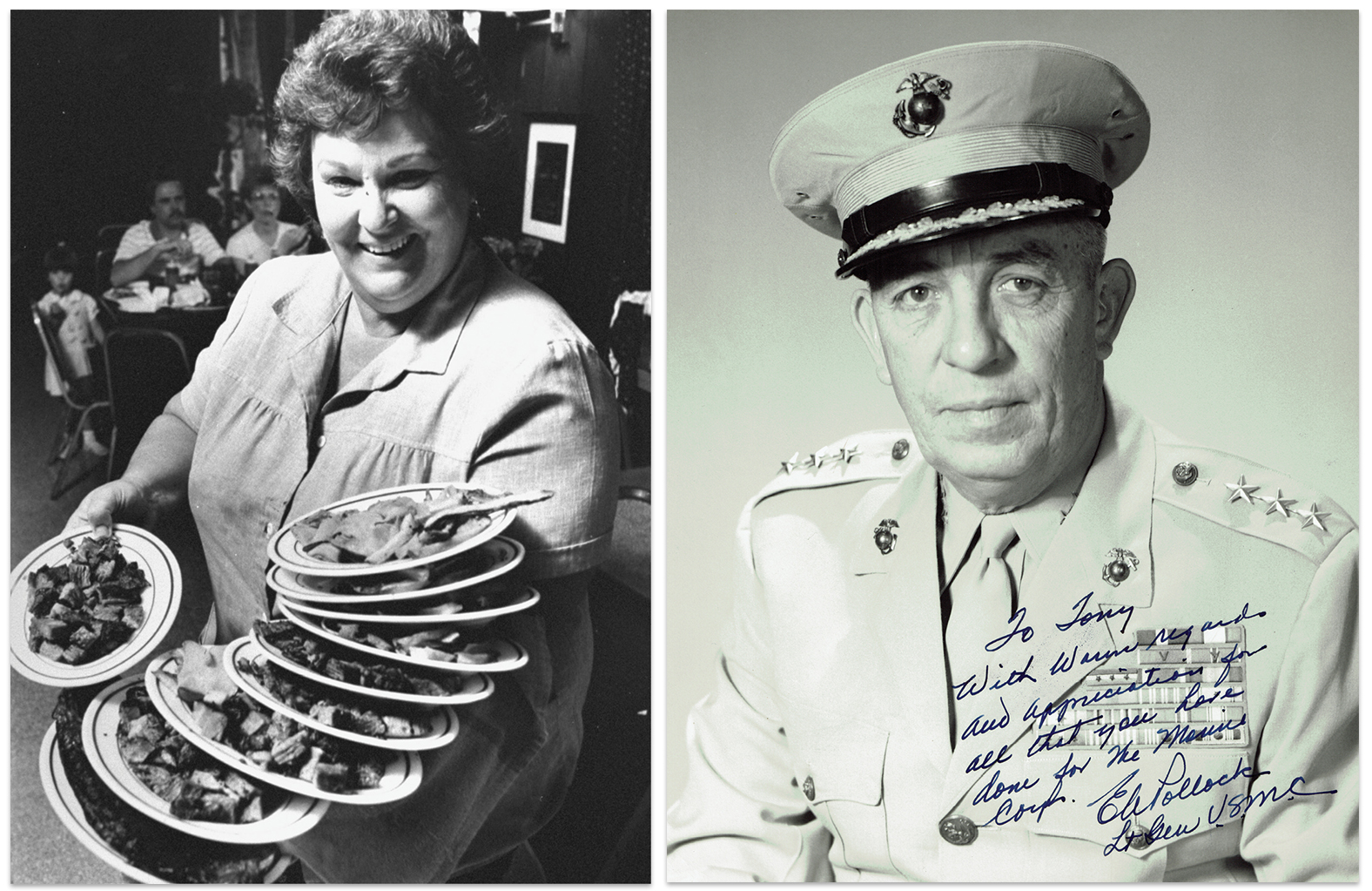

Dishing it out in the kitchen was my dad, cooking-sherry-drinking John Lance, and America’s virtuoso grillman Wild Bill Logan. Sometimes Cadillac Joe or Uncle Steve would pitch in if they happened to be in town, instead of cooking at Alaskan mining camps. Loaded plates were delivered by our own army of veteran hair-netted waitresses who could carry six and seven plates down their fleshy arms. As soon as a Marine butt hit the seat, his meal was on the way.

Our seasoned waitresses would endure off-color remarks with stoic dignity. Valerie, Novella, Mary Lou, Janell, Connie—all of them knew how to handle the occasional “wink, pinch or goose” without a flinch. These gals were way too patriotic to rat out a young Marine.

Marines don’t chew. They gulp their food like baby birds. Chewing takes time. Manners ain’t an issue. Speed is. Use your fork, spoon, knife, hands, feet—don’t matter long as you keep shoveling food in your mouth. No Muzak growling in the background, no jukebox and no conversation. Only the background din of clanking plates and the frothy unintelligible garble of drill sergeants.

Why all the big hurry? Never could find out.

On Marine days, my old man would motor his Willys down to the corner of 7th Avenue and Broadway, near the unemployment office, which was right next to the red dot store, a gathering place for the listless, lazy, unfortunates and backsliders.

He’d hold up his fingers for the number of additional helpers he needed for that day. Three or four curb-dwelling local legends would hop on the Jeep tailgate and ride off with Dad. A couple of hours work would get them a hot meal and some cash money. Maybe enough for another bottle of peach brandy and a pack of cigs. Then back on the corner of 7th and Broadway.

Hungry Hurry

Mary Lou West, our head waitress said, (and I believe her): “Pound for pound, a Marine can out eat any animal on earth. In one day they consume nearbout their weight.”

It astonished us how much they could eat. Amazed me even more they could eat at all under such conditions. Bark at me like that, my mouth full of food, and for damn sure my peristaltic movement’s gonna shut down and my bowel movement’s gonna kick in.

But I guess you get used to it. Kinda like eating anywhere in New York City.

Fifteen minutes after they were seated, drill sergeants would trombone, “FORKS HOWN! H’EYES FRONNN! FAAAAW OUT!!”

More blurry movement. Finished or not, every Marine would slam down their gravy-laced forks, swallow half-chewed wads, gulp down a last swig of milk, sleeve off their white moustaches, then fire up out of their seats into impressive rigid attention and absolute tomb silence.

On their way out, Marines were allowed to single-file by the cash register counter, not to pay for their meal but to buy a candy bar or magazine. Our candy counter was stocked to the hilt with Pogey Bait: Snickers, Baby Ruths, Butterfingers, Mars, Milky Ways, Mounds, Mister Goodbars, Lifesavers, Almond Joys, Heath Bars and, of course, Hershey Bars with or without nuts.

On the other side the aisle, within arm’s reach, was the magazine rack. On Marine days, this rack was stocked with the kind of reading that appealed to young men whose libido had been in cold storage for the past six months.

While the Marines were buying candy and True Detective magazines showing brassiered women tied to chairs, our waitresses swarmed all over the dining room like Ziegfeld dancers, cleaning dishes, wiping and resetting the tables. Readying the restaurant for the next charge.

These boot camp grads always bought enough candy to gag a sword swallower and enough girlie magazines to wear out both hands. They’d stuff their booty in their socks, pants and under their hats. Once through the line, there wasn’t no lingering outside. The drill sergeants would herd their platoon back on the bus while another busload was being shoved and screamed into the restaurant.

As soon as they boarded the buses, the drill sergeant assigned to their bus would stalk the aisle holding a duffel bag. He’d order them to “Surrender all unopened pogey bait,” referring to their uneaten candy bars, into the sack. This being the first time in six months they’d wrapped their hand around anything except their rifle, some would try to cram-swallow an entire Baby Ruth or Butterfinger right before the drill sergeant reached him.

The Heimlich maneuver, still years away from discovery, made for many friendly-fire casualties. I’m guessing hundreds of young Marines, airways jammed with half-chewed Baby Ruths or Heath Bars, became bus-floor casualties due to drill sergeants thinking they could soprano-scream a choking recruit into breathing.

Some would let their hormones get the best of them. Every now and then, a recruit would let the sight of a big-eyed woman in tight shorts or the thought of a cold beer temporarily lobotomize him. He’d AWOL off down 9th Avenue heading for the Pavilion or Bowery in search of one or the other or both. Head count on the bus is taken.

“JARHEAD MISSIN’!!!,” drill sergeant wails. Drill sergeants fan out like bird dogs. The suds-moustache recruit would be rounded up, thrown on the bus in handcuffs, his name parsed into anatomy parts and then maybe pounded on a bit.

In would swarm another two buses, another 150 Marines.

This military mayhem right in the middle of town was a big to-do. Myrtle Beach in the early ’50s was a three-month economy. Winter activity was as slow as a dry snail. Besides the Easter Egg Hunt, Pavilion Minstrel Shows, Halloween Festival, Christmas Parade and trout season, these weekly invasions became one of our off-season highlights. Locals looked forward to the coming of the Marines.

Fascinating Show

These were the days of Korea, 38th Parallel, Heartbreak Ridge, Give ’em Hell Harry, The Red Menace, Dwight D. Eisenhower and A-Bomb drills. Young men in crisp uniforms still fascinated the average American, still stirred emotions, especially the average Southern American. Some good-ole-boy elders—smelling of mothballs, Hadacol and liniment—would show up wearing their VFW hats and button-popping military shirts jeweled out in combat ribbons. They’d gather on the sidewalk to reminisce and salute while the buses unloaded.

The local girls were also fascinated.

Young, giggly girls in pleated skirts, dixie-cup bras, loafers and bobby socks, with that flirty glint in their eye, would congregate outside the restaurant to ogle at the hormonal sight of several hundred healthy young men lined like bulls at a cattle auction. A city block of manliness, virility and potential romance. More brazen girls would flip a recruit a perfumed paper wad with a lipsticked address, begging them to write or go AWOL.

Several of my grammar school pals would even show up. They’d come toting plastic pistols and rifles, wearing helmets and uniforms, with GI Joe comic books stuffed in their back pockets. They’d surround the waiting buses, stage mock attacks, shout marching orders and practice their salute as the Marines marched by. They’d chase the buses as they pulled out, yelling, “GUADALCANAL, IWO JIMA, AUDIE MURPHEY, SAN JUAN HILL, REMEMBER THE ALAMO!”

Being I could freely fraternize with drill sergeants and gyrenes, not to mention my dad had girlie books on his magazine rack and the songs “Rocket 88,” “Long Tall Sally” and Big Mama Thornton’s “Hound Dog” on the jukebox, provided me a certain status in the eyes of my pals. When we played Army, I was always the drill sergeant.

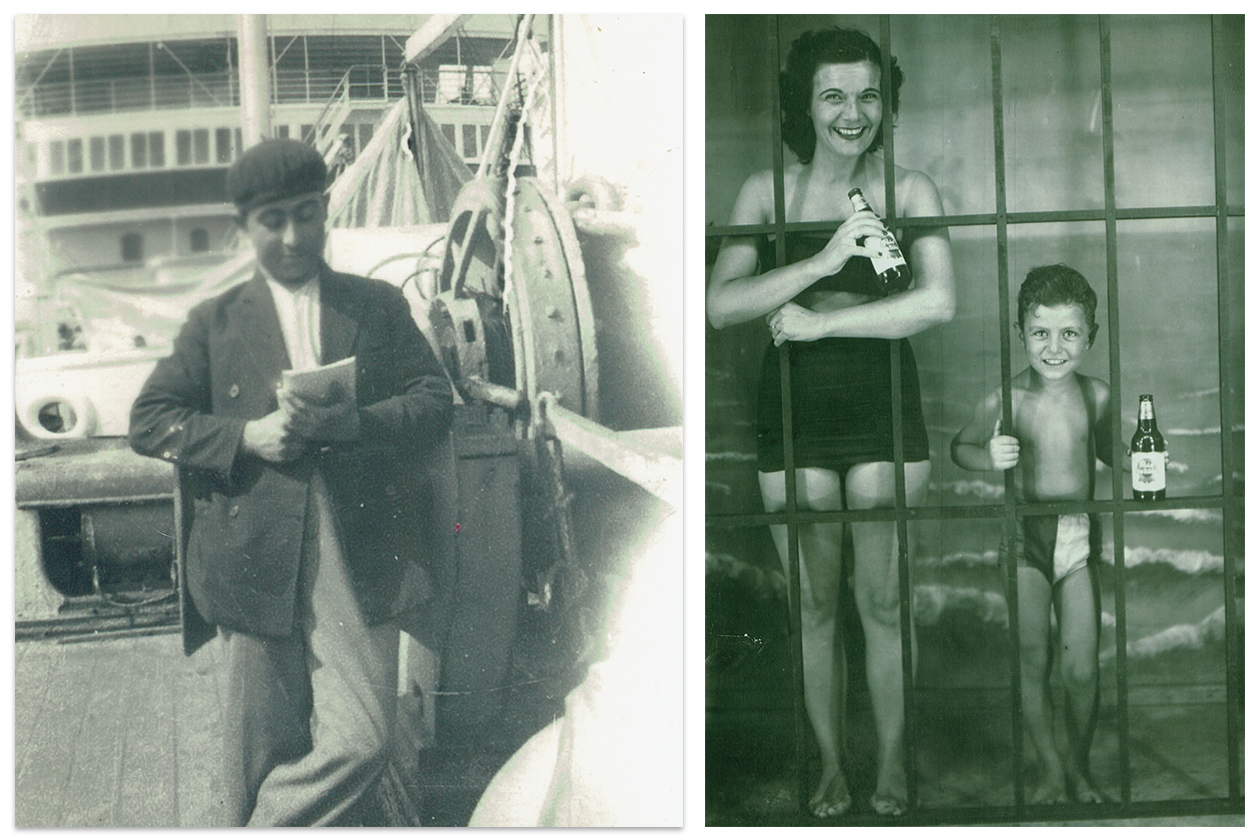

Many of the drill sergeants made the trip several times. It didn’t take long for my 5’6” Greek-accented, gregarious father to become military chic with them. On one trip the drill sergeants ceremoniously paraded Dad on the sidewalk and appointed him honorary drill sergeant. They presented him with a Field Sergeant Major shirt, complete with a dozen hash marks and a chest full of medals. I especially liked the rifle-range medal with the expert bar. They also gave him a campaign hat and a swagger stick, which they said was a short baton used as insignia and for jabbing jarheads in the ass.

From that day on, whenever Marines were scheduled, Dad would proudly pop on his Marine hat, put on his starched Field Sergeant Major shirt, grab his swagger stick and stalk through the dining room barking militarese along with the other drill sergeants. They didn’t bring him any trousers or shoes, so he always wore his white cook’s pants and corn-mealed kitchen shoes.

“How’s the chow, men?” Dad would yell. Greek accent.

“Fine, sir,” they’d roar back in unison.

“I can’t hear you,” Dad would yowl again. This time, Marines would thunder out a response at the top of their combat-ready voices, loud enough to rattle windows, scatter stray dogs and start the phone ringing at the local police station. The Marines, so programmed to react, never seemed to notice Tony was wearing white cook’s pants, spoke with a Greek accent and was the height of a shotgun.

Right after the last busload pulled out, he’d signal me to put away the girlie magazines and restock racks with Field and Stream, Life, Look, Mechanics Illustrated, and the latest comic books.

There was a certain pageantry to it all. Crisp uniforms, precision marching, bellowing drill sergeants (who became drill instructors in 1971) and roaring buses belching diesel. Even Tony’s military impersonations provided a welcome spectacle to our dwindling downtown. We once served 2,500 marines in three-and-a-half hours, an event still considered the Iwo Jima of food production.