A Day in the Life of a New South Brewer

While the famous quote “Beer is proof God loves us and wants us to be happy” is widely and incorrectly attributed to Benjamin Franklin (the quote actually started circulating anonymously on the Internet in the late ’90s), few can deny its sentiment. Beer is an ancient beverage; that much we know as fact. Some say the oldest recorded recipe of any kind, in the history of all humanity, is for beer. Archeologists and historians tell us the Mesopotamians brewed beer in 10,000 B.C., and the ancient Egyptians recorded their craft beer recipes on papyrus around 5,000 B.C. That’s pretty old, and proof, at least, that beer has delicious staying power, if not also God’s blessing.

Fast forward to 2020 A.D., and the craft beer boom that started in the 1970s and exploded in the ’80s and ’90s continues its unprecedented growth today—another 4 percent increase last year, even while overall beer sales are flat. According to the Brewers Association, there were approximately 1,500 breweries in the U.S. in 2008. Now there are more than 8,000, one of which, New South Brewing (NSB), sits in the heart of Myrtle Beach, and is owned by brewmaster and entrepreneur Dave Epstein.

While Epstein and his original partner, brewmaster Josh Quigley of brewpub Quigley’s Pint & Plate in Pawleys Island, started NSB some 21 years ago, Epstein is now the sole owner. After Epstein and Quigley parted ways, Epstein ran the operation himself, with only occasional part-time help. But like all good owner/operators, as the business grew, Epstein recognized no single brewmaster can make all the beer all the time. After a previous head brewer moved on, John “Jilly” Garner was hired as head brewer nearly five years ago. In my recent NSB visitation, I would get to speak with Epstein by phone and get hands-on time with Garner observing the intricate dance of the beer maker. While Epstein busied himself and his staff for a trip to the Great American Beer Festival in Denver, everyone worked fast and furiously to finish production on a new batch of brew before heading west.

7:30 a.m.

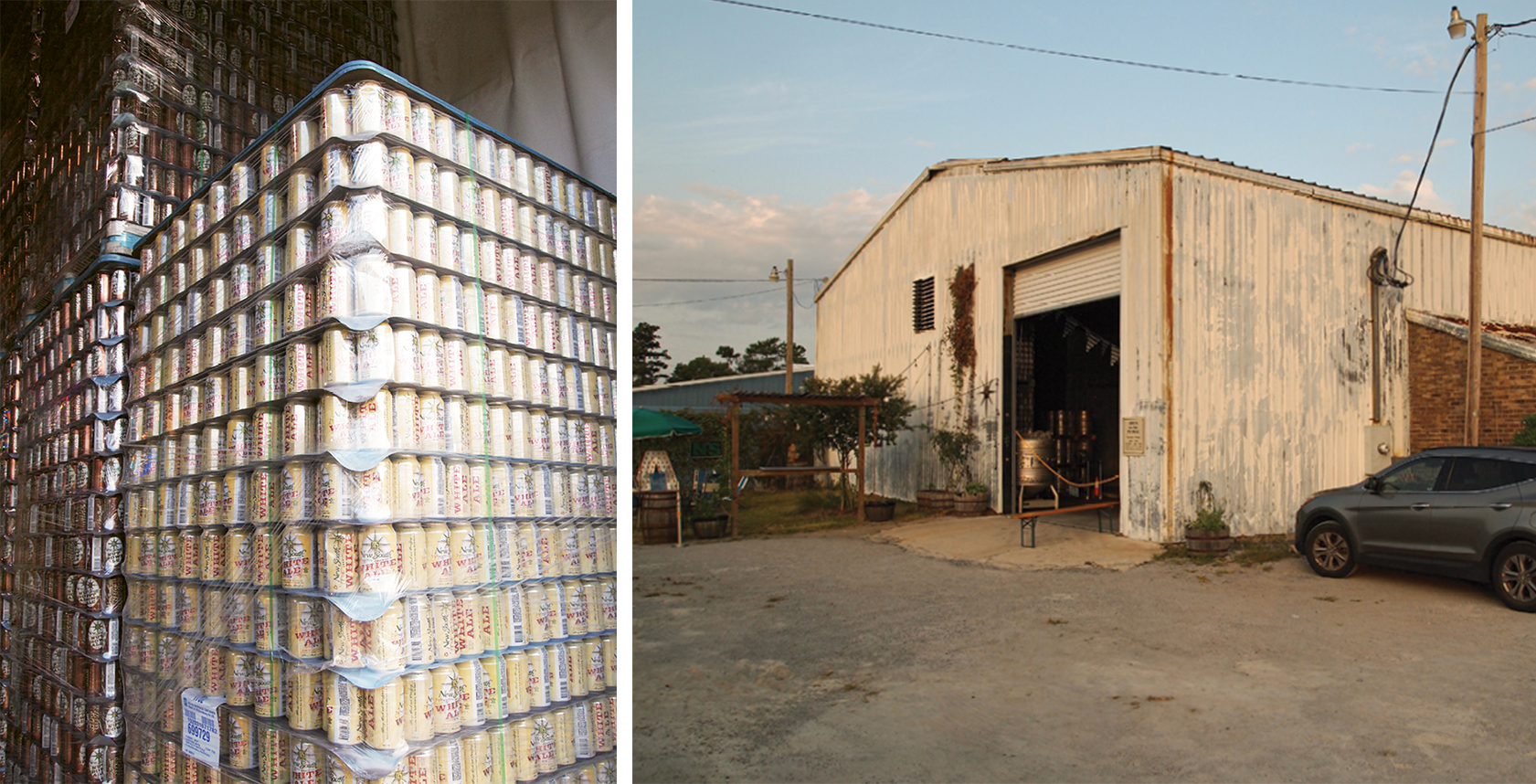

The sun has just risen over an old industrial neighborhood near the heart of downtown Myrtle Beach where beer warehousing (and now beer brewing) have a long history. I turn the corner past the massive Better Brands facility, a historic Anheuser-Busch beverage distribution center just off 10th Avenue North. I then wind my way through dusty side streets, past vacant lots overgrown with weeds and over top of long since retired railroad tracks surrounded by old metal sheds. It’s not a particularly scenic or pretty place, but it reeks of history, hard work and long days. Turning the corner to Campbell Street, New South Brewing quietly announces its quirky and unconventional presence with a small sign. A barely visible hand painted “Stroh’s Brewing” sign from a bygone era is faded into the side of the very same building, paying homage to the location’s venerable beer history.

The large warehouse and brewery side door is open and the large fans are running at full capacity. It’s already an unseasonably hot day, and brewing beer, I will discover, can be a hot and sticky affair.

Garner often starts his days brewing at the facility around 7 or 8 a.m. and, depending on the season and the orders, sometimes brews for up to an 8- to 10-hour shift before heading home. Garner also bartends on most Saturdays, along with his wife, Andrea, at the New South Brewing Taproom. The small pub is attached to the front of the brewery and is open to the public six days per week, closed only on Mondays.

The fans and machinery create a good bit of ambient background noise in what is otherwise essentially a mostly silent process. I find Garner with a sack of malted barley over his shoulder heading to the hopper. He greets me, we exchange pleasantries and start talking about beer and beer making. A longtime home brewer, Garner says he’s always been “super interested” in all that goes into brewing. It was a natural progression for him to move from New South customer to New South head brewer. A friendly fellow with a thick beard, ready smile and strong back, Garner moves sacks of grain and talks simultaneously. He’s brewing today and, while happy to share facts and stories about the brewery life, he can’t stop to chitchat once the process has begun.

7:40 a.m.

The day before a brew, Garner will check the recipe and stock of needed supplies. With some 15 to 20 possible versions of a brew, it’s essential to follow exact recipes and execute a dozen other critical brewing details, including the type and amount of grains, the temperature of the water and when to add extracts, all of which must be perfect to get a consistent, recognizable version of the beer they’re making. “Today I’m mashing in,” says Garner,” which means I open all the bags and then the grain goes up a small grain elevator.” He’s been preheating a mash tun, a giant stainless steel cauldron where the magic process begins by simply mixing grain and water. Today he’s making Nut Brown Ale, a very popular seller. “A darker malted barley makes the [amber] color and gives it its [fuller bodied] flavor,” he says. From tearing open the bags of grain to cold beer in hand takes about three weeks, and NSB rarely, if ever, stops production for more than a few days.

Garner, 47, grew up in Norman, Oklahoma, and went to the University of North Carolina, majoring in journalism and graphic design. For more than two years, he wrote the popular “Beer Man” column for the now defunct alternative weekly newspaper, the Weekly Surge. “I worked in my major for 20-plus years before taking on this job four-and-a-half years ago,” he says. Garner and crew must get caught up with brewing duties before heading to Denver. The Great American Beer Festival, a massive national brewer’s competition and beer lovers’ convention, has been running since 1982. Epstein, too, was excited about going. “We haven’t been in 17 years,” he would tell me. “We went our first three years, but this will be our first chance to return in a long time.”

Epstein, Garner and NSB production manager Roddy Graham, along with head of packaging Chris Barnes, will attend and host a booth at the convention, but today is all about brewing just to keep up with orders. “We only can our White Ale and Nut Brown Ale to go out to the grocery stores,” says Garner. Virtually all of the regional Food Lion, Publix and Lowes grocery stores (some 30–40 in the area) carry the NSB White and Brown beers. A dozen additional brews, including a higher than average ABV (alcohol by volume) Dirty Myrtle, get kegged and sent to some 250 bars in the region.

“We began as a contract brewer for Tbonz [Homegrown Hospitality Group,]” said Epstein. “They really gave us our start. We make all the [private label] beers for their 17 restaurants now.” Locally that includes Tbonz Gill & Grill, Liberty Taproom, Rioz Brazilian Steakhouse, Flying Fish Public Market & Grill and Taco Mundo.

7:50 a.m.

“I’ll keep the rakes running for about 30 minutes,” says Garner, as the metal arms rotating slowly in the mash tun mix the steaming ingredients, the air smelling of baked bread. He keeps close watch over temperature controls, adding gypsum (calcium sulfate) brewing salt and babying the infant Nut Brown Ale. He stands on an 8-foot tall platform to look in on the process, while I hover over his shoulder.

Below us, Chris Barnes, who’s been with NSB for four years, is sterilizing beer cans and preparing for a daylong process of canning and turning White Ale into six-packs, each and every can filled individually by hand. “We’ve done more than 300 cases in week before,” remarks Barnes, 27, who is well suited to the task, as is part-time canner Brian Smith. Barnes, native to Myrtle Beach, had been at Coastal Carolina University and Horry-Georgetown Tech studying to be a history teacher. He said after interning and meeting some of the high school kids he’d be teaching one day, he decided he wasn’t cut out for the profession. Here, in the daily company of a just a few like-minded beer enthusiasts, he’s happy and content and growing with the company. He’s one of just a few full-time employees at NSB.

8:01 a.m.

Surrounding us, large cone-bottomed fermentation tanks sit quietly while yeast eats the things it loves. Others hold filtered beer, ready to be kegged. Large vats of caustic detergents used to clean the vats between brew cycles are a reminder of the process and hard work of brewing, canning and cleaning that takes place just about every day.

The audio from a live concert video of the Allman Brothers adds to the unique sounds of NSB at full steam, Warren Haynes’ guitar riffs bellowing in the din. “If not the Allman Brothers, then it’s Widespread Panic,” remarks Barnes. The public image of NSB, from its hand-drawn logo to its psychedelic-inspired paraphernalia and clever beer names, perfectly matches the fiercely independent bohemian attitude of independent beer makers. Their defiance of the corporate, colossal industrial brewers is evident in all they do.

“We are a microbrewery, an independent craft brewery,” explained Epstein, “separate and distinct from the crafty sounding breweries and labels actually owned by the big guys. The big guys have muddied the waters, and it’s important to us and the Brewers Association that we keep our separate identity.”

Still, Epstein, like everyone who’s ever visited the massive Sierra Nevada Brewing Company location outside of Asheville, N.C., can’t help but be impressed with its size and scale. “Sierra Nevada is the most beautiful brewery I’ve ever been in,” he said. “We’ve gotten to know the brewmaster, and everybody there is cool, and they have a great reputation among employees. It’s nice when you have $300 million to build the perfect [large scale] brewery. It’s magnificent. It’s amazing. I really love it.”

Nearby neighbor Better Brands is also a distributor of NSB beers, along with their flagship Anheuser-Busch (Budweiser) brands, a comingling of small and large interests that seems to work for everyone.

8:35 a.m.

Pallets of barley, wheat and dried malt extract sit near the entrance to the largest part of the giant warehouse, most of which is used by Homegrown Hospitality, the building’s owner and NSB’s landlord. Garner takes me through the warehouse, past old Tbonz Gill & Grill signs, to the back door.

“This is like our employee lounge,” he says. A quarter-acre treed lot with hammocks, a fire pit, garden, disc golf and tables and chairs sits ready to host breaks during the day, and employee and casual business functions when time and weather allow.

The front “yard,” open to the public, is adorned with old signage, tables and chairs and cornhole games. Food trucks will park there when the taproom is open and during peak times to help feed those who drop in for a beer or two.

When asked what his favorite NSB beer is Garner answers “Dirty Myrtle. It’s a recipe Dave and I hammered out and it became an immediate hit.” Second only in sales to NSB’s flagship New South White Ale, Dirty Myrtle is an American Imperial Double IPA with an ABV of 8.9 percent, almost twice the alcohol by volume of an average beer; Budweiser and Bud Light, for example, both have an ABV of 5 percent, with Michelob Ultra at 4.2 percent. Dirty Myrtle is hop-forward in flavor, meaning you can really taste the hops. It’s a light honey-gold color and considered “full bodied.” This beer consistently earns high marks from craft beer lovers.

9:30 a.m.

While the brew is brewing and the canners are canning, Garner sits at the bar in the taproom to work on the NSB website. As a trained journalist and graphic arts professional, this work, like the brewing, is second nature.

The website lists beers currently on tap, including the bourbon barrel-aged Big Wooly Mammoth, an Imperial Stout with an ABV of 10.5 percent that’s stored in actual bourbon barrels before being kegged. A calendar lists the taproom hours and any other seasonal events. “We pride ourselves on offering an eclectic experience,” Epstein told me, “with different than typical Myrtle Beach kinds of activities. We’re doing yoga on Sunday mornings [11 a.m.–noon]. We call it ‘Namaste For A Beer.’” The $10 fee covers the yoga session in the brewery and includes one beer in the taproom at the session’s conclusion.

Garner tells me that the rest of the morning through afternoon will have NSB staff continuing their ritual duties, not unlike the beer-brewing evangelist monks from 1,500 years prior.

4:30 p.m.

The doors have opened to the New South Brewing Taproom. A few tourists are the first in. This surprises me, as NSB is way off the beaten path; the average tourist (and local, for that matter) would never see NSB in daily travels. “People seek us out on the web,” said Epstein. “Most of our taproom business is from craft beer lovers who purposely look for us.” The bar, which looks like any other small bar anywhere in America, offers some 10–13 NSB beers on tap, and several other varieties canned for carry-out, available only at the taproom. An added bonus, on Saturdays Garner is bartender. This means beer lovers get unlimited access to the guy who’s made the beer they’re drinking. He regularly holds court behind the bar, answering questions, making recommendations and seeing firsthand the enjoyment his brews bring to those who stop by.

Misty-eyed and thoughtful at the prospect, God only knows how many young visiting homebrewers Garner and NSB have inspired to abandon medical school, quit teaching or leave the clergy, all in the pursuit of making the world’s oldest brewed beverage. After all, it’s a time-honored profession, and one that may enjoy a divine right.

Celebrating its 21st year in business, NSB will host a “Finally Legal Party” sometime in late fall or early winter, or whenever they decide it feels right.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY OF NEW SOUTH BREWING