Take a walk through these solemn grounds and history will flow over you.

The quiet solitude of a cemetery belies the incredible history that is virtually being shouted from the graves. We in the Grand Strand have an amazing wealth of history hidden in our various cemeteries–from large, formal and well-maintained graveyards to small family plots to hidden gems that have become overgrown, fallen into disrepair and, in some cases, nearly lost to the elements and development.

From Calabash to Georgetown and west to Conway, there are hundreds of final resting places that have rich and varied stories to tell us. Many are associated with neighboring churches that are rich in history and architecture. All are within a 45-minute drive on the Grand Strand and many are closer than we realize. Take a quiet walk through any of these solemn grounds and the history will flow over you like a warm shower.

Ben Burroughs is director of Horry County Archives at Coastal Carolina University (CCU). When asked how many graveyards there are in the county, he says, “We don’t really know. There are literally thousands in Horry County and on the Grand Strand. Take a simple ride in the country out past Aynor or Longs or Bucksport and you’d pass countless farms and homesteads, many of which have their own small family plots.”

Some of these cemeteries are lovingly cared for, while, unfortunately, many others have been abandoned and have fallen into disrepair.

Burroughs has a massive job maintaining and managing county archives at CCU, but he has a special affinity for the history and genealogy of our area. He can trace his own family back at least six generations. Several of his kin are buried at a small graveyard in Tilley Swamp off Highway 90, north of Conway. The plot dates back to at least 1830 and contains the remains of Burroughs’ great-great grandfather Jo≠≠hn Cox, his son Josiah Cox, his wife Elizabeth Wilson Cox, and various descendants, including Burroughs’ grandmother.

The history and folklore surrounding these places is truly epic. Take, for example, the Kingston Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Conway, a beautiful, well-maintained plot on Third Avenue, just one block east of Main Street. It is on the National Register of Historic Places. A little girl named Elizabeth Singleton was buried here in 1815 and her slate marker stone is one of the oldest and best preserved in the area.

Thomas Beaty and his wife Mary Brookman Beaty are buried here as well. He was a wealthy plantation owner, newspaper editor and lawyer. His death during the Civil War was the result of “friendly fire” when the local militia went into the swamp south of town to defend it against approaching Union soldiers. He was accidentally shot by an ally in the confusion.

Tragedy stalked this family–all five of the Beaty children died young. Two of the sisters died of diphtheria. One of the other daughters was swimming in a pond near the house and began to drown. Her older sister went in to help, followed by a servant girl, and all three drowned. The youngest and only son, Brookie, has become a Conway ghost story. Brookie was ill in bed and his mother was in the parlor when she heard beautiful music. Her dead daughters appeared to her as angels and told her they had come for their brother. Mary went to Brookie’s bedroom and found him dead. All five children are buried in the Kingston Cemetery.

There is an old slave cemetery in Surfside Beach that has largely been destroyed by development. However, the Surfside Beach Historical Society is working hard to preserve what remains of the site. The property sits between two homes on Cypress and Juniper Drives and is filled with trees. Other houses toward South Myrtle Drive may sit on parcels of the cemetery. The entire area was once the Ark Plantation, which spanned nearly 3,200 acres.

Joyce Suliman, president of the historical society, says, “We have over 50 death certificates that we have found. We’ve had two radar tests done with the county. Both times they found burials.”

Ben Burroughs adds, “The cemetery dates back to pre-Civil War years, with burials as recent as the 1950s. Back then, they didn’t have caskets, especially for the blacks buried in Surfside.”

The Ark Plantation House was at the intersection of Third Avenue South and South Willow Drive Now, it’s an empty lot filled with large live oak trees.

The oldest cemetery within the City of Myrtle Beach is Oak Street Cemetery, located directly behind the Myrtle Beach Convention Center and the Health Department on 21st Ave North and Oak Street. This cemetery has the graves of hundreds of African Americans, and most of them are unknown with only a few markers. The Myrtle Beach Neighborhood Services Department is holding fundraisers to conduct research and find names for unmarked graves.

Another very old and hidden historic cemetery is in a wooded tract off Route 904 and Route 66. Just one-eighth mile off the road there is a turn-off, where history buffs can park and explore. The cemetery has only four tombstones, which are nearly unreadable, and two posts that indicate there may have once been a fence. An old sign reading “Pondfield Cemetery” is nailed to a tree.

Another small but historically important cemetery is St. Mary’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church Cemetery on Green Drive in Pawleys Island, just off Route 17. This small plot is shaded with trees and other growth but contains numerous graves of slaves and their descendants. Mack Alston, Jr. (April 4, 1927-December 24, 2014), a graduate of Howard High School who played in the National Football League for the Redskins, Oilers and Colts, is buried here.

From the late 1600s up to the years just before the Civil War, Georgetown was an important seaport thanks to the rice, indigo and cotton trading that occurred there. Georgetown actually rivaled Boston, New York and Philadelphia for wealth and influence in that era. Because of its growth and importance, several churches and cemeteries were established that still exist today.

One of the most significant of these churches is Duncan Memorial United Methodist Church and the Old Methodist Cemetery at 901 Highmarket Street. It is the oldest Methodist congregation in South Carolina. The church was established in 1785, shortly after the American Revolution by Bishop Francis Asbury. He was one of several “circuit riders,” or preachers who traveled the region on horseback, spreading God’s word and establishing the Methodist religion. William Wayne, a local merchant that Asbury converted, gave his home and land for the church and cemetery.

The cemetery contains six of the region’s oldest graves–the plots of six of the itinerant Methodist ministers all born in the late 1700s and died in the early 1800s. The oldest known grave here is that of the Rev. Anthony Senter, dated 1817.

Nearly one-third of the graves are for children under the age of 12, which underscores the rugged life and contagious diseases that haunted early settlers. Also located there are 22 graves belonging to soldiers of the Confederate States of America, some killed in action and others who served and died later, as well as the grave of one Union soldier.

A few blocks away at the corner of Highmarket and Broad streets is Prince George Winyah Parish and Cemetery. It is one of the oldest continuously operating congregations and church buildings in South Carolina, having celebrated its 300th anniversary in 2021. This cemetery sits next to the church behind an impressive brick wall and is very well maintained. There are more than 1,100 graves here, including Confederate Brigadier General James Heyward Trapier (1815-1865) and Paul Trapier (1749-1778), a member of America’s Continental Congress.

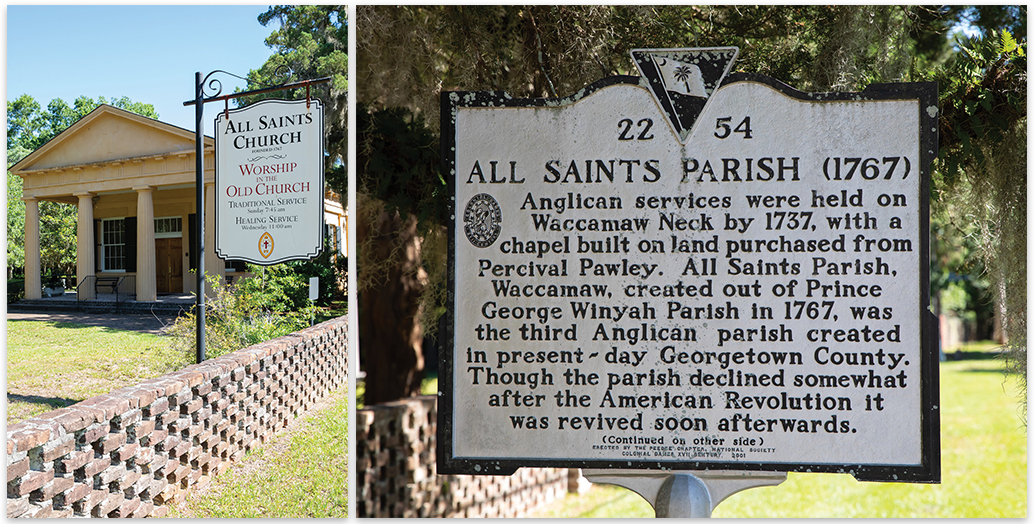

Another historically significant church and cemetery is All Saints Church in Pawleys Island. This historic church complex and national historic district is located at 3560 Kings River Road in Pawleys Island and consists of three buildings and one site: the sanctuary, rectory, chapel and cemetery. In 2004, the congregation left the Episcopal Church to join the Diocese of the Carolinas, now part of the Anglican Church in North America.

This congregation was started in 1739 and is another of the state’s oldest continuously operating parishes. The cemetery was begun around 1820 and contains the graves of numerous public figures of Georgetown County. It also features outstanding examples of gravestone art from the 1800s and is enclosed by a brick wall with wrought iron gates.

Buried here are Benjamin Huger (1768-1823), a U.S. congressman and John Ashe Alston (1817-1858), a rice farmer and Brigadier General of the South Carolina Militia in 1844. Alston’s grave monument is noteworthy and features a large obelisk with heraldic imagery. A more recent notable grave is that of Carroll Ashmore Campbell, Jr. (1940-2005), former governor of South Carolina from 1987 to 1995.

Christine Vernon of Murrells Inlet is an expert on local history and lore. While children call her “The Pirate Lady,” Christine is actually a performing artist and storyteller who focuses on local h=istory and legends. She has been doing walking tours in Murrells Inlet since 2015. Her husband, Paul, who has lived here more than 40 years, is also a history buff and was a close friend of Mickey Spillane.

“I strive to maintain the rich history of our area through storytelling and acting,” says Vernon. “My programs pay the utmost respect to the deceased and their resting places. I don’t dabble in conjuring or silly ghost tales, but work hard to communicate the history of the Grand Strand, especially to our young people.”

Vernon explains that the entire area of Garden City and Murrells Inlet was named Wachesaw by the local Native peoples of the Waccamaw tribe. The name means “The Place of Great Weeping” because there are so many buried here. She said there are countless “lost” graves all over the area, including members of the tribe and those who were plantation slaves.

One of Vernon’s most popular tours is along the MarshWalk. She generally does not tour in the cemeteries themselves, although she has done a few private tours there. Near the MarshWalk is Belin Memorial United Methodist Memorial Church, which sits right on the shoreline in Murrells Inlet and has a small cemetery across Business Route 17. The Rev. James Lynch Belin, who died in 1859, and a few of his family members are buried here. Many other family members are buried at All Saints Cemetery.

Belin’s father had been a plantation owner, but James wanted to become a Methodist minister. The church denied his request because the family had slaves. James offered to divest most of his land and holdings, with the last 100 acres going to the church after his death, so the church agreed and he was ordained.

Vernon also notes that, over the centuries, hundreds of unknown people have been lost at sea and to local flooding events and have never been found or buried. The most dramatic incident was in 1893 when a 30-foot high storm surge swept over the area that is now Huntington Beach. The Flagg family first took refuge in the upstairs of their house, but then were forced out of the windows and into the trees. Teenager Ward Flagg hung on for dear life as he watched his parents and siblings succumb to the torrent. He was the only one to survive and was found hours later by rescuers. Ward later became a doctor and served the area around what is now Brookgreen Gardens.

So, the spirits of those who came before us are not only in the numerous cemeteries around the Grand Strand, but many are resting where they were lost and never found. If you want to get the flavor of the rich history of the Grand Strand, take some time to visit one or more of these sacred places, especially those off the beaten path.

Silent Cities

Brookgreen Gardens offers a popular excursion of cemeteries on its property titled “Silent Cities.” This guided tour is a rare opportunity to travel on back roads and pathways in the most remote areas of Brookgreen Gardens, where three plantations once existed. The tour explores three cemeteries and attendees learn about the historical burial customs of European and African origin. Dozens of interesting gravesites are included. Tickets for this two-hour tour may be purchased online or at Brookgreen Gardens and are in addition to regular admission.

Attendees are cautioned that the tour vehicle travels over rough dirt roads. It is not recommended for persons with back or neck health issues or other physical issues. There is approximately a mile of walking over dirt roads, paths, and through wooded areas. Due to the nature of this tour, children under the age of 12 are not allowed.