A Day in the Life of Dr. Dan Abel, CCU’s Shark Whisperer

Our fascination with sharks probably goes back to the dawn of humanity, as most shark species—at least the ones that haven’t gone extinct—have remained largely unchanged for some 400 million years, and they always seem to draw a crowd. They come in many shapes and sizes, from the dwarf lantern shark at less than foot long at maturity, to the whale shark at 40 feet. Nearly all shark species look menacing to most of us, though that’s an assessment Coastal Carolina University’s Dr. Dan Abel would emphatically reject. Abel and his CCU marine science students have been studying, catching, tagging, releasing and appreciating these magnificent creatures for nearly 25 years.

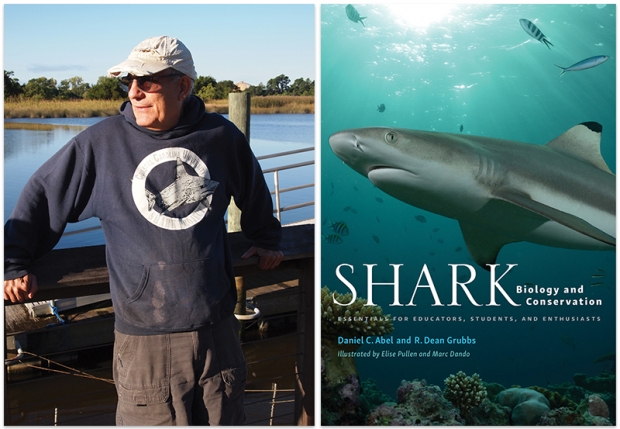

Abel, who’s written textbooks on the subject of shark biology and conservation, and countless articles and research papers, has a new book, aptly titled SHARK Biology and Conservation.The book has been well-reviewed by those in the field, many of whom are Abel’s colleagues and former students, and all who know a thing or two about these often misunderstood animals.

As many shark species are apex predators at the top of the marine food chain, sharks have been given a “bad rap,” says Abel.

The motion picture franchise Jaws, the made-for-TV Sharknado and Shark Week series haven’t helped either. Due to overfishing, accidental death known as “by-catch,” which is the unwanted harvesting and destruction of sharks while fishing for target species, and the inhumane and wasteful practices by some who insist on eating shark fin soup, it’s estimated that, since the 1970s, the world’s shark population has decreased by some 70 percent. That’s not good for any of us—especially the sharks.

Having been given the opportunity to attend a shark tagging expedition with Dr. Abel and nine of his students one recent fall day, I was eager to learn more about CCU’s program, what the process looks like, and why it matters to Dr. Abel and the world that we maintain healthy shark populations where they exist and restore them where they’re threatened or endangered. We started our day at the docks along Georgetown’s Front St., where my first thought was… “We’re going to need a bigger boat.”

8:30 a.m.

The CCU Research Vessel I finally spot tied up in front of the honkytonk Georgetown bar, Buzz’s Roost, is not the hulking, impressive, 50-foot gunmetal gray ship I’ve seen before, but instead a humble 30-foot pontoon boat, sitting just a few feet above sea level.

“That other boat isn’t really useful to us for tagging,” says Dr. Abel, the Marine Science Professor who’s called CCU home for nearly three decades. He spots my skepticism. “This is the boat we use. It’s the perfect size for what we do.”

Abel greets his students and guests, all arriving at the dock on a sunny, cool morning. We make our way on board, anticipation growing.

8:45 a.m.

After final preparations are made, we’re all aboard with our captain, a first mate, Dr. Abel, his lead graduate students, a few undergrads, and guests, including WBTW’s Meghan Miller—onboard shooting video for a series on micro plastics and their impacts on marine life and sharks in particular.

Dr. Abel, a native of Charleston and longtime resident of Pawleys Island, earned his Ph.D. in Marine Biology from the University of California San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. He also studied at College of Charleston and was a postdoctoral fellow at MUSC. Devoted to conservation and ecology, he is an avid environmentalist, writing textbooks and sitting on a variety of boards dealing with everything from forest protection to the ecology of the world’s oceans. He’s taught several sessions for The Semester at Sea program, affording him the opportunity to see much of the world.

“To think that I got paid—not very much, mind you—to sail around the world and teach…” he muses.

8:55 a.m.

“Today we’re doing two research projects; testing two protocols; looking for environmental DNA to indicate the presence of sharks and testing smart-hook technology, designed to reduce by-catch by fisherman,” Abel says, as the captain readies the boat for departure.

“There’s been a precipitous decline in shark populations from even just seven or eight years ago, largely because of by-catch. Fishermen who are after Mahi, swordfish and tuna are indiscriminately also catching sharks, and they don’t survive these encounters,” he continues. “ We’re testing new magnesium hooks designed by a former student of mine. When exposed to saltwater they emit a slight electrical charge, but one we hope is enough to discourage sharks from biting.”

Over the course of 27 years, Abel has seen a number of his students continue in the field and gain reputations as excellent scientists and marine biologists.

“My students have become so famous–it’s a little annoying,” he laughs, before sipping coffee from a cherished, lucky thermos. “Today we’ll be tagging, hopefully, the most common shark in Winyah Bay, the sandbar shark. They’re one of the most gorgeous beasts on the planet. They have that big dorsal fin, so easy to work with.”

I had never considered that some sharks would be “easy to work with,” or what that even means, but I took his word for it.

9:00 a.m.

As if on cue, Captain Edwin Jayroe focuses the attention of the boisterous crowd of students and guests on board. He discusses basic boat safety, life jackets, which by now we’re all wearing, and he points to the head, the toilet, tucked away in the corner of the deck behind a closed door.

“It’s nothing but a port-a-potty, but it works,” he laughs. We were planning on being out in Winyah Bay for several hours, and it was good to know where to go.

After a few more announcements from the captain, Dr. Abel takes a serious stand.

“The most important thing to remember while on this boat is, don’t touch my coffee, unless it’s about to go overboard.”

This is a serious scientific research project, but Abel keeps the mood light. It’s apparent his students not only respect him, but like him, and he them.

“Actually, safety is the most important thing aboard the boat,” he adds. “There’s a lot of activity and a lot of moving around, but we know what we’re doing. The graduate students will show you and tell you everything you need to know. They are in charge.”

The captain brings the boat to idle speed along the Harborwalk and waterfront of historic downtown Georgetown. We pass the gap in the buildings at 700 Front St., where eight historic structures burned beyond repair in 2013; their absence still felt eight years later.

Beyond Georgetown’s history and attractiveness to visitors, it’s also a working seaport with limited commercial shipping and commercial fisherman adding to its nautical charm. We pass shrimp boats, most docked and not out because the seas just beyond Winyah Bay are too rough on this day. I don’t get seasick, but not knowing what to expect, I’ve taken two Dramamine seasickness pills, and I will be glad I did.

9:10 a.m.

Reaching the end of the waterfront district on the Sampit River, Captain Jayroe picks up speed and we notice a distinct chop on the water not evident moments earlier.

“We’re supposed to have calmer seas today than we had yesterday,” says Abel with a skeptical grin, “but I don’t know.”

Our destination is a known feeding ground near the mouth of the Bay, where sharks have been caught in abundance on other trips.

“We caught seven yesterday,” he says, “but we could get skunked. After all, we’re fishing, and any fisherman will tell you, ‘you don’t always get you’re looking for.’ ”

9:20 a.m.

The little boat skips happily over the chop, while students ready the longlines, hands wrapped around fish heads and other fishy body parts baiting the sharp, barbed hooks.

“The first thing we’ll do is check the bottom salinity, and then we’ll throw out three, maybe four, longlines today,” says Abel, who has conducted between 500-600 tagging cruises, just like the one we’re on today.

A longline is a strong rope with baited hooks on short steel lines placed every 10 feet, 25 in all, per line. Bright orange buoys on each end help the researchers keep tabs on the longline’s location.

“We’ve had large sharks break the line, or drag the buoys hundreds of yards,” says Abel.

9:35 a.m.

One student counts marks on the line yelling out “Mark!” every time one slips through her hands. I tell her that’s how Mark Twain got his name when working on a Mississippi riverboat. She nods politely and smiles, but can’t stop to chat. While the students finish baiting the longlines and are busy deploying the first of three, I ask Dr. Abel, “Why the Winyah Bay?

“Other shark species are predominant in our area coastal estuaries,” he answers, “but we think there’s something special about Winyah Bay. It’s big enough that there’s protection from bigger sharks–most of the sandbar sharks we tag are young, not sexually mature, and the biggest threat to these sharks is other sharks. They’re offered some protection here, and because there’s lower salinity in the bay, bigger sharks don’t like the water as much. Occasionally a larger, mature shark will wander in and figure out where the good feeding is, but not usually.

“We catch, tag and release all the sharks we work with,” he continues. “We’ve only killed twice, and that was because of a micro-plastics study we were doing and there was no other way.”

9:40 a.m.

With one longline deployed, Abel and the Captain discuss where to set the next. The day is pleasant, but the wind is up and the seas are running three feet.

“This is really too rough,” says Abel, as the boat rocks from side to side during slow-speed maneuvers.

But that doesn’t stop fisherman in boats half our size from trying their luck just a couple hundred yards away.

With a break in the action, I ask Dr. Abel about his teaching style.

“I do lecture,” he says, “but it’s the least effective way to teach the subject. I can teach anything out here.”

On cruise days, Abel is up at 5 a.m. to prepare and recheck weather and marine forecasts. Surrounded by all the fish, I ask him if he’s a seafood lover.

“I’m a strange bird,” he answers. “I call myself a ‘pescavegan.’ I don’t eat animal products, no dairy, but I do eat fish, somewhat reluctantly.”

I get the feeling that Abel takes his personal conservation ethos seriously. He does.

“I almost exclusively study sharks in my scholarly work, but I’m also a tree hugger from way back, so I study sustainability. It’s hard to work with animals and not care about every living thing on the planet.”

He doesn’t get the same warm-fuzzy as many of us do when we see a shrimp trawler, an iconic image of Carolina coastal life.

“Dragging trawl nets on the ocean floor is akin to clear-cutting a forest,” he says. “They literally scrape the bottom. Look, commercial fishing is one of the hardest, most dangerous jobs in the world, and no fisherman I know wants to destroy the environment. They just want to earn a living.

I’m sympathetic to them, but there are things we can do, even little things,” he continues. “Insist on eating local shrimp, for example. Many [area] restaurants buy and serve imported shrimp, but it comes from places where they destroy the mangrove swamps for the aquaculture.”

These are just some of the issues outside Abel’s primary scholarly work.

“The co-author {R. Dean Grubbs} of my book is probably the finest shark biologist on the planet,” says Abel. “I wanted him to write the book, but he never did, so I said, ‘I’ll write it and you help me and contribute, and edit.’ It has been a couple of years in the works. It’s not a coffee table book, and it’s not a text book. We tried to hit a sweet spot in between what would be of interest to my undergraduates, the graduate students, educated enthusiasts and naturalists. It’s selling well, with lots of 5-star reviews. We’re happy about it.”

10:12 a.m.

“Hold on to something!” yells a graduate student, as the third longline is deployed, and we come about, rocking pretty hard.

We motor to the location of the first longline deployed, and one of the guests is given the honor of hanging off the bow of the rocking boat and capturing the buoy and line with the help of a boat hook. Once secure, with gloved hands, she begins to haul the line in. The first bait and hook are intact with no shark attached. Twenty-four more to go. Hook after hook is empty, a few are missing bait, but on this first longline, not one shark.

“Hey, it happens,” says Abel,. “We got skunked with the National Geographic team aboard filming a while back. Luckily, they could stay another day, The next time out we got six or seven.”

We motor to the second line and Dr. Abel tries his hand at hoisting in. At the seventeenth hook, we’re rewarded with a 3-foot, 6-inch sandbar shark. He’s a juvenile male, 4 or 5 years old and is feisty but surprisingly “easy to work with.” I ask if the “Baby Shark” song is ever sung at a time like this and am met with boos from the students.

“We call this the ‘Jacuzzi’,” says Abel, pointing to the large plastic tub filled with about 18 inches of seawater pumped from Winyah Bay moments earlier. After a struggle to remove the hook–it required pliers and three students to do this–no one lost any fingers or blood in the process, including the shark.

Every student is afforded the opportunity to retrieve the shark from the Jacuzzi, and hold it up briefly for a photo. Then, the shark is laid prone in a specially designed troth for tagging.

A small, pointed awl drives a thin barbed wire with a numbered passive tag attached (these are not electronic trackers) just under the skin. The tag number is recorded in a notebook, the numbers are double-checked, and the little guy is returned to the bay.

“We occasionally recatch sharks that we’ve tagged years earlier,” says Abel, “and that’s important data. We can track their movement, health and growth over a specific time. Sandbar sharks are threatened, but recovering. Since they don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re 14 or 15 years old, the trajectory to bring them to pre-exploitation levels is 40 years. But with the climate warming and acidifying of the ocean, along with the micro plastics, it’s hard to know.

“This shark was caught on the test hook,” he adds to his students.

I comment it must be disappointing and proof they’re not working, but Abel has data on the project. “Actually, the hooks work, just not 100 percent of the time.”

“This guy is a bit smaller than average, but it’s what we expect,” he says. “We’ve had a 10-footer on board this boat before. He was really too big to handle and we kept him on the bow.”

10:40 a.m.

As the third longline is hoisted aboard, we cross our fingers for another sandbar shark, but no luck.

“Not a banner day,” says Abel, “but at least we didn’t get skunked.”

11:00 a.m.

As we make our way back toward the dock, I ask the Doc about his memories as an educator and plans for the future.

“I really love my job,” he says, “especially when I’m out with the students on the water and we’re doing good work. You can’t underplay the educational importance of this trip. We’re in a beautiful ecosystem, we’re looking for strands of shark DNA in the water, we’re tagging sharks and we’re testing smart-hooks.”

He looks out over the bow of the boat and searches his memory.

“The Semester at Sea experience was rewarding, too, but now I’m thinking about retirement in a few years. I’m 65 years old,” he says.

“What will you do?” I ask.

“Write–I’ve got at least one more book in me. Maybe rekindle my love of playing the jazz flute.”

Snapped back to the present, Abel re-focuses on the task at hand: “Yes, the students learn about sharks, but they also learn about their role as responsible citizens, about sustainability, the conservation message and how to live reasonable and sustainable lives on this planet we call home. That’s a big part of my goal.”