A day in the life of Travis Carroll

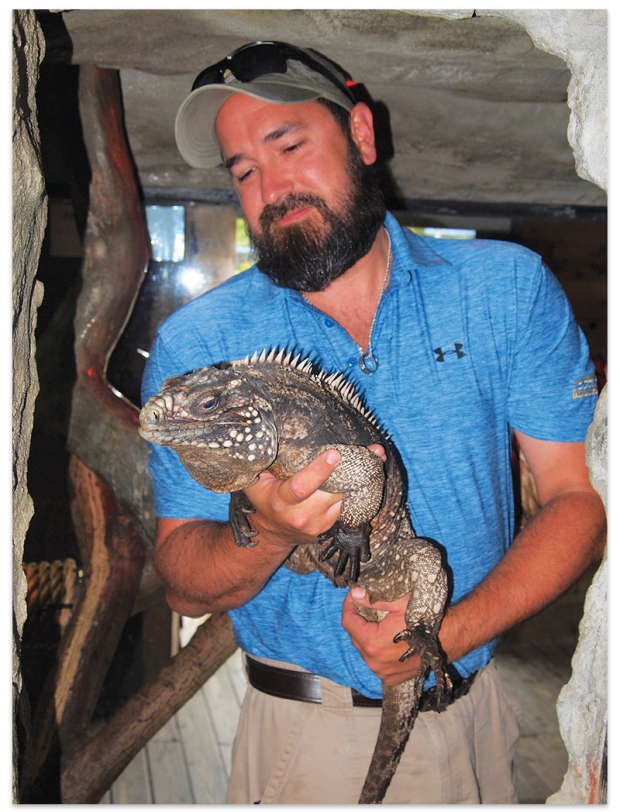

Often the first to arrive at 7 a.m., and sometimes the last to leave, 39-year-old Travis Correll, the Zoological Operations Manager for Alligator Adventure in North Myrtle Beach, knows what it takes to keep the animals in his care happy, healthy and well adjusted; something zookeepers call “enrichment.” He also knows he can’t do it alone. A small army of staff work the 15-acre attraction, and share Correll’s commitment to the wide variety of species at the zoo and the enjoyment of the zoo’s guests.

Correll, who’s worked full time at Alligator Adventure since he was 15 years old, considers himself part of the family of lemurs, crocodiles, cats (large and small), hyenas, birds, reptiles and, of course, alligators. He’s patiently listened to and answered every question asked by guests, and even intrusive journalists tagging along for the day.

7:02 a.m.

As we pass by Utan (pronounced OO’-tan), “The King of the Crocs,” and the largest animal of his kind in North America (likely one of the largest in the world), I start with the dumb questions.

Q. How long can Utan live?

A. No one knows. He’s a hybrid.

Q. OK, how long can alligators live in captivity?

A. Well, Utan is not an alligator.

Q. Oh, right. Then, how about crocodiles?

A. Utan is not a [standard breed of] crocodile, either.

This continued for a moment until I figured out how to ask the question properly.

“Utan is 58,” says Correll, “and he could easily live to be 100. Nobody really knows about this breed. He’s a hybrid between a saltwater croc and a Siamese croc.”

Utan and his siblings were raised at a croc farm south of Bangkok, Thailand, where the two species accidentally co-mingled, and produced these oversized animals. Utan is around 20-feet long and weighs around 2,000 lbs. He’s been at Alligator Adventure since 2002, and lives in a 5,000-square-foot enclosure with a 30,000-gallon private, freshwater pond, and he is priceless.

We will get up close and personal at his feeding later. Now, two hours before the gates open and an hour before the majority of the staff arrives, it’s time to start cleaning and feeding the zoo’s other residents.

7:15 a.m.

It’s quiet at the zoo in these hours before guests arrive, a time when it’s a joy to see the animals and learn about them from the guy best suited to the task. The only noises come from the occasional exotic bird squawking from some unseen part of the attraction. Though the day is still cool and sunny, it will get warmer and much louder gradually over the next several hours.

“These are some of my favorites,” Correll says as we neared the bobcat exhibit. “I hand raised these guys from kittens.”

Correll works through a series of tasks well-practiced over a 25-year training period. In a matter of minutes, the exhibit is cleaned, the cats have plenty of fresh water and a few toys, and a special breakfast is served. I learn that bobcats live in the wild in every U.S. state, except Hawaii.

“But you’ll never see one in the wild,” he says. “They’re very shy.”

The habitat is double-checked and the cats seem happy. The food, toys and interaction fall under the general term “enrichment,” a word I would hear over and over throughout the day from the zookeepers I would meet. Enrichment might be food, it could be toys, it could be a new giant log from which to perch; it’s any and all of the things that come together to make life for the animals as stress-free and fulfilling as possible.

It seems zookeepers, the good ones anyway, have learned something over the course of millennia, since the first zoos were created in Egypt around 1500 B.C. Spawned by growing exploration of the world, man’s fascination with dangerous wildlife and the desire to interact with it safely, zoos are at their best when the animals are happy and healthy—a daunting task. Today’s best zoos follow best practices, including a certain minimum amount of space required for each habitat, strict veterinarian care (mandated and required by law for accreditation), and the zoo must meet, and should exceed, the standards for psychological enrichment and stimulation of the animals in its care.

The residents of Alligator Adventure may not be living in their natural habitat in the wild, but they are well cared for and have formed bonds with their zookeepers. In some cases, the animals are an endangered species, or are rescues with no chance of survival in the wild.

7:18 a.m.

Our next stop is the ring-tailed lemur habitat. Four of these little guys and gals are curled together and sleeping as we approach. They watch us curiously, yawn and rub their eyes, waking up in much the same way as most primates. Seeing them at this time of day, you might almost expect one of them to ask for coffee and a danish.

“When they do wake up,” says Correll, “they like to ‘Move it! Move it!’,” referencing the song that King Julian, a ring-tailed lemur, sings from the Madagascar movie franchise. “Almost every kid that visits the lemurs will sing it to the animals.” As we walk throughout the attraction, all eyes are on us. The animals are keenly aware that we’re there, and it’s easy to wonder if they’re studying us as much as we study them. I’m reminded of the American humorist, Evan Esar, who was quoted as saying, “The zoo is an excellent place to study the habits of human beings.”

Correll pressure washes the lemur’s habitat, scrubs the food dishes, empties and refills the small pond in the enclosure and leaves food for the somewhat shy animals. Then, we’re off to our next task.

7:35 a.m.

I discovered quickly that the day in the life of a zookeeper is not all YouTube cuddly animal moments. With hundreds of potentially very dangerous animals at the attraction, including alligators, crocodiles, cougars, hyenas and the most dangerous bird in the world, a cassowary, there’s a lot of protocol to follow and no room for error. A zookeeper’s day is spent feeding the residents, answering guests’ questions and cleaning up the poo… a lot of poo. Correll and his staff are unfazed by the dirty part of the job because, they say, the rewards make it worth it.

When asked about his work history at the attraction, Correll relays how fate intervened when he was just a lad.

“When I was 15, I won tickets from a radio contest to see my favorite band, Green Day, at the House of Blues.,” he says.

The prize included a meet-n-greet with the band and a guided tour of Alligator Adventure.

“When Billy Joe [Armstrong, of the band] joked to the owners that they needed to ‘give this kid tagging along with them a job,’ the manager told me ‘be here this weekend and we’ll get you started.’ That was like, 24 years ago.”

“I was a bit of troubled kid,” continues Correll. “The owners [father and son, Sam & Jake Puglia] treated me like family, took me under their wing, gave me full-time work and I’ve never looked back.”

He pauses for a moment, and turns toward me. “If I had not won those tickets, I probably would not have worked here, and would have never met my wife [Kerri Quick-Correll]. We’ve been married now for two years and have a beautiful baby.”

The couple’s son, Travis Rex Correll (T-Rex for short) is just over 1 year old.

“We take him everywhere with us,” he says. “He’s our little adventure buddy.”

7:40 a.m.

We pass another exhibit with a pair of much larger primates belonging to the same general family of those we just left.

“The girls on staff here insist on unofficially naming all the animals,” says Correll. “This is Mr. & Mrs. Claus.” He introduces me to a pair of ruffed lemurs. A few minutes later, after rounding the bend, an unearthly howl penetrated the relative quiet and sent a chill down my spine.

“That was them, Mr. & Mrs. Claus,” explains Correll, before I even have a chance to ask.“ They have that loud, deep scream; it’s their call, and when they get going, you can hear them for a long distance.”

Black and White Ruffed Lemurs are critically endangered, and are native only to Madagascar. They yell again.

“You think that was loud?” Correll asks, a grin on his face. “You should hear them in an enclosed room, like if they need veterinarian care. It’s just unbelievable.”

“We are a USDA Accredited Zoo,” adds Correll, “and we’re inspected regularly for our exhibits having the right amount of room, and that we offer the right enrichment, our dietary plans are reviewed, as is our veterinarian documentation.”

At the facility since its inception, vet Dr. Sam Seashole (aka “The Croc Doc”) has been instrumental in the welfare of the animals in his care and has a veterinarian practice in Moncks Corner, S.C. “You could almost say he was a co-creator of Alligator Adventure back in 1995.”

7:50 a.m.

Correll steps into the exhibit space of the zoo’s cassowary, recognized as the world’s deadliest bird. He’s a brightly colored, 4-foot-tall flightless bird, with feet that look remarkably like those found on velociraptors, including the single 5-inch central dagger-like claw that can easily eviscerate and tear through flesh—something we all learned from Jurassic Park.

“Frank and I go way back,” says Correl.

He has respect for Frank the bird, and keeps his distance while tending to its needs. The cassowary can hit speeds in excess of 30 mph, and jump as high as 5 feet from standing.

We move toward the center of the attraction, but not before the ruffed lemurs scream again, sending my coffee flying. Correll finds humor in this.

8:00 a.m.

“So, you can see,” says Correll, “when I get here in the morning, I like to go throughout the facility, make sure everything’s up to speed, no animals on the loose, no flooding, whatever. Checking for anything and everything. When the staff arrives before opening, we like to wake up the zoo, continue the cleaning and feeding. There’s still a lot to do.”

With most of the opening animal staff now on the premises, Correll has to tend to administrative tasks, which leads me to zookeeper Breanna DeCriscio. We meet at the large cougar habitat.

“Cougars, mountain lions, pumas are all different names for the same animal,” says DeCriscio, who is a recentCoastal Carolina University (CCU) graduate, putting her biology degree to good use.

“I’m a science nerd,” she says as I follow her into the enclosure, where two big cats spend each night.

I am in awe of these animals, which eyeball and sniff me through the chain link fencing that separates us. They are just giant housecats, with the same traits as their smaller, and somewhat safer, domesticated cousins. They’re cute, fluffy, and potentially deadly, and so are the cougars. DeCriscio triple-checks the order of doors opening, closing, and ensures that locks are firmly in place. Safety and protocol share the number one priority at the zoo.

DeCriscio points to a pan of large meatballs she’d prepared just before our meeting, and we walk out into the secured habitat, the pair of cougars still in their overnight home.

“We put these meatballs out as enrichment,” she says, “and kind of hide them just a little, so they have to smell for them and find them; like an Easter egg hunt.”

She picks up poo, waters grass, and finally sprays some liquid from a pink bottle on the rocks and trees, even near the meatballs.

“This is just cheap, non-toxic perfume–just fragrance and water,” she explains. “We spray different scents in a new places. Again, it stimulates them. Cats like to smell new things. They love to rub themselves in the perfume. We want them to be happy, active and engaged.” And, apparently, smelling extra fresh. Enrichment.

As we let the cougars outside, the female hisses at me. Being hissed at by a full grown and hungry cougar is a sobering experience. If you think housecats can be terrifying, the fear factor goes up by 50 when the housecat is 220 pounds of muscle and teeth.

9:05 a.m.

After a thorough cleaning of the cougar habitat, I’m met by another young zookeeper, Evan Hendrickson, also a recent CCU bology graduate. He takes me to the kitchen’s food prep area, where I meet a few more staffers. Many are still in their early 20s and alumni of CCU, which has been sendiing their graduates to the zoo for decades.

The high-quality produce Hendrickson is chopping is fit for human consumption. Fruits and veggies of almost every sort, but with specific nutritional characteristics, are prepared for some of the primate, reptilian and avian residents of the zoo. The alligators and crocodiles eat fresh, whole chickens, but Utan will later receive a special treat to the delight of the crowd there at feeding time.

I follow Hendrickson to the Flamingo habitat, which is in rough shape, at least before he shines it up. “Birds are gross,” says Hendrickson, hosing down the enclosure, while the flamingos look on from across a pond. “They eat and poop. A lot.”

Hendrickson finished his undergrad education at CCU and has been applying to veterinarian schools with his heart set on North Carolina State University.

“I hope to be a vet one day,” he says, as leads me away from the flamingos and passes me on to zookeeper Megan Bright.

9:45 a.m.

I follow Bright into a heated room filled with file drawers. This is snake country. Dozens of snakes stay here when not part of an exhibit or show on the adjacent stage. The zookeepers-turned-lecturers take turns presenting a short, 20-minute show that includes large snakes, Q&A, and the finale, the friendly capture of a baby alligator.

Still in the enclosed room, Bright checks the feeding schedule and delivers juicy, thawed rats—from tiny-sized rodents, to ones the size of your fist. The snakes snap at the food dangled at the end of feeding tongs, and slink back into their drawers for digestion, which can take days.

This is no place for the squeamish. “This isn’t the grossest thing we do,” says Bright. “Sometimes they’ll eat rats and regurgitate them, and it doesn’t smell or look so great.“

Bright dons her wireless headset mic and prepares for the lecture. People gather on the shaded bleachers and wait for the live show, which runs on the hour. Bright engages with the crowd, answering questions, giving pop quizzes and shooing baby gators back into the water.

I run into zookeeper Hendrickson after the show and ask about all the little gators.

“All the gators are segregated by size,” he tells me, “the babies with babies, juveniles with others their same approximate size and age, and full grown gators [mostly]peacefully coexisting. They are cannibal animals, so they have to be separated.”

10:30 a.m.

The zoo is busy, but I’m told it’s a slower day.

“When the zoo is closed, it normally takes me two to three minutes to walk from front to back,” says Correll. “On busy days, it can take me 10 minutes or more.”

We travel to the Galapagos Tortoise habitat and meet the two residents: one, a 55-year old youngster, and the other, a baby in his teens. Both are enormous, and both can expect to outlive everyone who’s ever visited the zoo. These gentle giants can live to 150 years. Today, they enjoy a Caesar salad, minus the anchovy dressing.

The next hour is spent touring the rest of the zoo, watching the gators throughout the park feed on whole chickens, and a spectacular big show held on the main lagoon. I also meet a few of the attraction’s other residents, including Bob, a gator born without a tail, who would have never survived in the wild. We meet Six-Pack, a turtle with an hourglass figure caused by a constricting six-pack plastic ring carelessly discarded and entangled mid-body. Before his rescue, this turtle would have died. A rare albino alligator, who came from Louisiana as a baby, lives in his own shaded sanctuary. He is full grown and protected from the deadly sun, but not from the thousands of awestruck visitors who marvel when meeting him.

11:30 a.m.

As Correll rounds the bend with a bucket of steak, $75 worth, I’m invited to watch Utan’s feeding. “He also eats whole, skinned rabbits from time to time,” says Correll.

To even watch Utan lay in repose is awe-inspiring, but to see him move draws the admiration of the crowd gathered at the fence. Correll has hand fed Utan countless times, but each feeding is done carefully. Even though Utan seems docile, he is an evolutionary ambush predator, who can store up energy for days and weeks, and let it surge at the right moment. You want to make sure you’re nowhere near Utan’s business end when that “right moment” occurs.

“Utan is definitively the largest [croc] in North America,” says Correll, “and one of the largest in the world. Utan and I have done this dance for what? 16 years now?”

12:05 p.m.

After the feeding, I have a last chance to chat with Correll, and he shares more of his story. When he started at Alligator Adventure, he was given basic facility cleaning duties, but not much with the animals. “After a while, I’d say ‘Hey, you need help with the alligators?’ and they’d let me help with some small job. Once they trusted me and I had a little training, they put me to work all over the zoo. It’s a great job. And unlike working at other big zoos, where a zookeeper has one animal type and works in one area of the zoo, we get a lot of hands-on, with a lot of different animals, and we all love that.”

Alligator Adventure is located at Barefoot Landing in North Myrtle Beach. Call 843-361-0789 or visit www.alligatoradventure.com for more information.