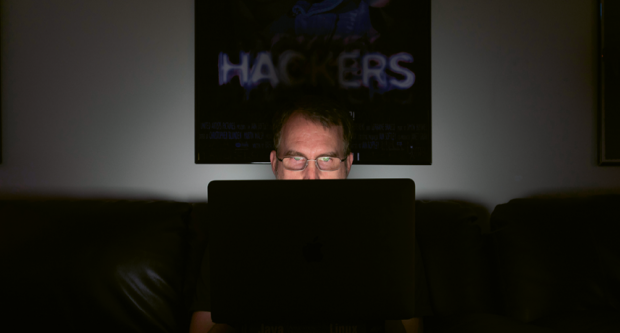

How a computer security analyst is saving the planet (and millions of dollars) one large hack at a time

Back in the early ’80s, when a 13-year-old Joe Stewart was jonesing for the Tandy Radio Shack TRS-80 that was wheeled into his sixth grade classroom, he would’ve done anything for the hackerspace his adult self founded a few years ago right here in Myrtle Beach.

“Yeah, these are the kinds of resources I wish I’d had back then,” says Stewart.

He’s giving a tour through the two-floor building tucked into an old industrial park that houses Subproto, an experimental hybrid hacker/maker space, where anyone with a passion for building, taking apart, fixing and hacking software, and much more, can meet, connect, learn and ultimately make a difference. There’s a maze of high-tech gadgets, such as a 3D printer, a workbench to prototype electronics, a biohacking lab, a laser cutter, a CNC machine and a full tool shop for larger scale fabrication, plus a second floor “hacker lounge” that doubles as a virtual classroom.

“Back home, in this small town in Arizona, I didn’t have much money, little in technology as far as books go, and I was starved for the resources and knowledge,” says Stewart.

His goal when opening Subproto was to open the proverbial door to these technology opportunities for those with the drive and motivation but without the money or the parts. He happened upon the hackerspace movement on a business trip to Austria and the rest is history.

“You can read about stuff online all day long, but if you can’t get your hands and play with these things, you won’t really know if it’s possible,” says Stewart. “Here they can break things to learn how to fix things. If I had one of these places growing up, I would’ve never left and who knows where I’d be now.”

Stewart tells of the one time he nearly didn’t leave, in fact, a computer store on Main Street that had just opened in his hometown. Anytime he could get his hands on a keypad, he’d try to sit down and program something until he’d finally have to come up for air.

“One Saturday, I must’ve been there for like eight hours,” he says. “And before I left, the store owner came over to tell me kindly not to come back. He said, ‘Yeah, love what you’re doing, but you’re scaring the customers because we’re trying to tell the customers how easy these computers are to use, but then they see what you’re doing and … so could you not come back?’”

Stewart could finally sit for hours in front of a computer from the comforts of his home after his persistence in begging his father for one paid off in the form of a Commodore VIC-20, the cheapest home computer you could buy at that time.

“I’d monopolize my time on that thing,” he says. “Computers to me have always been very intuitive … I can just pick up things quickly on it. I’d try to hack together a game or write some sort of software.”

It was these bits of bytes that would surge, route and reroute Stewart—in his own unique way—onto the pathway to his success today. What began as an interest in computer security, which he once thought would be a boring day filled with sifting through spreadsheets (a mistake in hindsight, based on what he does for a living today), shifted to a desire to dive into a career in electronics. This was until he learned from living with his electronic engineer older brother that a heavy course load of math is required (a course that’s not really part of his equation). He ended up enrolling in Warner-Southern College, a small college in Lake Wales, Florida, to study communications. He promptly dropped out a year later.

“I’m not really good with directed learning schools—I’m very much a self-learner,” says Stewart. “But if I’m interested in something, I can absorb it very quickly.”

One big thing he did take away from that one year in college was his wife, whom he met the first day of orientation and married a year later. The newlyweds moved into a one-bedroom trailer next to the college until she graduated, while Stewart went on to work at Lowe’s Home Improvement for the next six years in both Florida and Myrtle Beach, where they moved to be closer to his wife’s family.

1996 marked the momentous year Stewart linked up with a Linux user group (Linux is a Unix-like operating system that launched in 1991) while dabbling on his mom’s old Intel 386 computer. It was an integral network that would lead him from a charged interest in the security and server admin work he was doing for a local web hosting company to a phone call he received from LURHQ to recruit him (thanks to a referral from that Linux user group member) as a computer security analyst, a position he went on to hold for the next 17 years. LURHQ, now SecureWorks, grew from a tiny startup out of Tony Prince’s garage in Loris to a multi-million-dollar company that’s gone public.

From day one at SecureWorks, Stewart dug deep into firewalls, dissected malware, retrieved millions of dollars for victims and garnered national attention from The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, thanks to the research and articles he published on the company’s website. His job description: to outhack the bad hackers like a superhero undercover agent.

“I hack for the good guys,” says Stewart. “It’s all about finding the loophole, whether for good or bad. ‘White hat hackers’ get the bad guys and protect the innocent victims, because it takes a hacker to catch a hacker. Law enforcement is great and they can kick in doors, but they don’t know the technical side.”

His strategy is something he calls “offense in depth,” a sort of sting operation that involves proactively going on the inside to peel off the layers of the hacker’s operation by invading their routine without them actually knowing it. How? It’s not easy, as malware criminals or state-sponsored hackers from Russia or China have mastered the art of hacking.

“They’ll set up infrastructure all over the world and they’ll bounce their connections to different computers to disguise their work,” says Stewart. “So I’ll pretend to be one of their infected computers—one of their victims—run their malware, wait for them to connect in, and then watch when they go out so I can read what they’re doing. You really need to know the malware and be able to reverse-engineer it.

“Within the last year or so, I’ve been tracking crime groups out of Nigeria, too,” he continues, “who have had this shift from those phony emails to more sophisticated wire transfer interceptions between businesses or homebuyers… I’m tracking several groups right now and these guys are stealing millions. Some would be stealing millions more if it weren’t for me.”

As of several weeks ago, Stewart left SecureWorks to work for a new California startup called Cymmetria, a cyber deception company that’s revealed an even newer branch of security that defends a network rather than going on the offense.

“No risk, no reward,” he says of the job switch. “It’s really an exciting opportunity and this strategy hasn’t been explored much.”

Stewart also admits that, contractually, it frees him and allows for him the possible opportunity to start up his own computer security company. He also just started a new company, Splyse, which essentially will support ideas and products with the most marketable, commercial potential out of the hacker and maker creations at Subproto.

“It’s a way to keep talented people here,” says Stewart. “Over the last three or four years, we haven’t been able to keep members here because they have to move to a bigger market for work.”

Aside from his day job, Stewart is also busy pitching prototypes to WonderWorks and planning the evolution of Subproto from a 50-member hackerspace to a nonprofit that has the ability of applying for grants to fund more educational programs and a full-time staff in a bigger freestanding space.

“It’s important to me to gain that connection to middle schoolers, because that’s where this all started for me,” he says. “That age is the perfect mix of curiosity and ability, without the influence of social expectations. With that ‘no fear’ factor, they pick up things fast as learners.”

Subproto’s youngest member is 15; she’s a maker in the middle of building her own drone right now, he says.

As a self-taught computer security expert, Stewart knows all too well that when you have the drive and motivation the future is deep and wide. He’s flying his 23-year-old daughter, also a college dropout genius, out to a “BioHack the Planet” conference in California for her birthday in August.

“It’s all been confined to academic research for so long and now people are figuring out that you can make these experiments,” he says. “This is stuff that wasn’t possible 10 years ago.”

Watch where he’ll make it and take it all in the next 10 years.

For more info on Subproto, visit www.subproto.com.