Winyah Rivers Alliance works to keep rivers swimmable, fishable, and drinkable

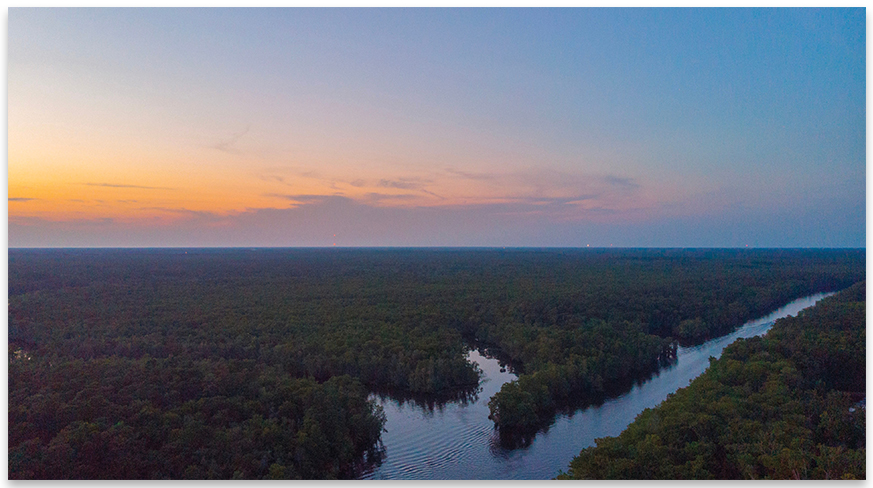

It is easy to forget that we live in the third-largest river basin in the Eastern United States. Unless your work, business, or daily activities are directly related to pursuits on the water, many of us take this important resource for granted.

The Winyah Bay near Georgetown is the coastal estuary that receives freshwater from nine significant rivers: the Waccamaw, Black and Sampit, and Greater Pee Dee, which is fed by the Lumber, Little Pee Dee, Lynches, Yadkin and Uwharrie. This basin covers 11,700 square miles and drains freshwater from as far away as the Blue Ridge Mountains. The Waccamaw Watershed covers 1,640 square miles, the Lumber Watershed covers 1,750 square miles, and the Black/Sampit Watershed covers 2,200 square miles. The only watersheds that are larger on the East Coast are the Chesapeake Bay and the Pamlico Sound.

The Winyah Rivers Alliance is an assembly of “riverkeepers” dedicated to protecting our rivers for fishing, swimming, boating, recreation, and the many daily uses of clean water in our homes, schools, and businesses. This alliance works to educate and encourage stewardship of our river resources. They safeguard against numerous threats to our clean water, and conserve our land and water for the benefit of our families, wildlife, and our future.

With a stated mission to “protect, preserve, monitor, and revitalize the health of the lands and waters of the greater Winyah Bay watershed,” the foundation was incorporated as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization in 2001. It began as a grassroots outfit of people from North and South Carolina dedicated to watching over the watershed and has grown significantly in the past 20 years.

The Winyah Rivers Alliance hosts the Waccamaw Riverkeeper, Lumber Riverkeeper, and Black-Sampit Riverkeeper programs. These programs are licensed by Waterkeeper Alliance and they partner with Waterkeepers Carolina. Waterkeeper Alliance is a global network of people – waterkeepers – who are dedicated to preserving and maintaining clean, unpolluted water sources. The organization focuses on three key areas of concern: 1) clean and safe energy; 2) strong environmental regulations; and 3) fighting pollution from large-scale industrial meat production. Waterkeepers advocate for compliance with laws, respond to citizen complaints, help identify problems and remedies, and educate the public.

Debra Buffkin is executive director of the Alliance and leads a staff of six along with hundreds of volunteers. The Alliance is guided by a dedicated 12-person board of directors and operates with an annual budget of $390,000 supported by numerous grants and awards.

“My primary objective as executive director is to keep everyone involved with the Alliance working toward our mission to protect the lands and waters of the greater Winyah Bay watershed, also known as the Lower Pee Dee Basin,” says Buffkin. “Our staff, riverkeepers, dedicated volunteers, and board members make up a formidable force keeping these rivers ‘swimmable, fishable, and drinkable.’ ”

Buffkin explains that one of the primary areas of focus for the Alliance is the protection of wetlands.

“I share in this passion with our riverkeepers to protect the rivers and wetlands because most of the days of my youth were spent fishing, water skiing, and swimming in the Little Pee Dee River where I grew up,” Buffkin says. “I know firsthand how the wetlands not only provide habitat for amazing creatures, but also aid in flood protection, purify water, and provide an open space to relax and enjoy the beauty of the natural world. We believe in protecting these open spaces for future generations!”

Buffkin quotes the famous environmentalist John Muir, who said, “The rivers flow not past, but through us, thrilling, tingling, vibrating every fiber and cell of the substance of our bodies, making them glide and sing.”

One of Buffkin’s primary goals for the future of the Alliance is to have a riverkeeper on each of the rivers the Alliance monitors and protects. Presently, they have a Waccamaw riverkeeper, Lumber riverkeeper, and a Black-Sampit riverkeeper. She plans to add a Little Pee Dee, Big Pee Dee, and Lynches riverkeeper(s) within the next few years.

Buffkin’s deputy director at the Alliance is Christine Ellis. Ellis has been with the Alliance for more than 16 years, initially as the Waccamaw riverkeeper, then to establish the Lumber riverkeeper Program, then as executive director, and currently as deputy director.

“I support our executive director in fulfilling our mission and helping secure needed funding to protect our local rivers and the benefits they provide to our communities and economy,” Ellis says.

She raises the volunteers, members, and donors who have supported the river and land protection work since 2001, and who continue to embrace the vision to ensure clean water and healthy, thriving communities in the watersheds.

Ellis adds, “My objective is to ensure that the good work of our riverkeepers is financially supported. I invite individuals and businesses to get connected to our nonprofit by donating time, expertise, and dollars to keep our local rivers fishable, swimmable, and drinkable, and our communities and economy thriving.”

The riverkeeper for the Waccamaw River is Cara Schildtknecht.

“One of the things I enjoy most about my role is hearing river stories,” Schildtknecht says. “Everyone has a story to tell me about the Waccamaw River, whether it is the time they saw river otters playing at a landing, how they have fished the river since they were a child, or the first time they paddled a kayak. Hearing these stories and engaging with our community members is the most rewarding part of my job. It reminds me why we protect clean water – so that everyone can have a river story.”

Schildtknecht explains that connecting with others and learning their stories helps her protect the river by sharing passions and creating a network of clean water stewardship throughout the watershed. She engages the community in a variety of ways, from guiding paddlers on the river to presenting scientific data to stakeholders, or visiting school classes, civic clubs, and organizations.

Being a riverkeeper is not a one-person job.

“It takes an entire community to make a difference and I am lucky to have the support of so many,” Schildtknecht says. “Without our dedicated and passionate community members, my job would be impossible. Our community helps us test water quality, clean up the rivers and landings, promote clean water stewardship, and serves as our eyes and ears on the water. We all work together to protect clean water in the Waccamaw River.”

The riverkeepers are critical to the successful implementation of the Alliance’s mission. Each one takes responsibility for the care and monitoring of the entire length of their assigned river and its bordering ecological habitat. This means managing a large team of volunteers and looking after the health and cleanliness of hundreds of miles of river basin. They take regular water samples, conduct cleanup events, and monitor for any large-scale threats, such as chemical spills, agricultural runoffs, fish kills, abandoned watercraft, and more.

Emma Gratto is assistant riverkeeper for the Lumber and Waccamaw rivers in North Carolina.

“The main focus of my role is to develop a volunteer monitoring program on the Lumber River,” says Gratto. “Water quality monitoring is necessary to identify sources of pollution and to implement remediation projects to improve water quality. Using volunteers for monitoring helps us extend spatial and temporal coverage of the program. We can cover many more river miles using volunteers than with staff alone.”

Gratto says that the Alliance is partnering with the University of North Carolina at Pembroke (UNCP), where students have begun monitoring the Lumber River watershed. Students are being trained to sample for parameters, including dissolved oxygen, pH, nutrients, turbidity, and fecal bacteria.

“The students are currently helping to build a baseline of data that will help identify illicit discharges into the river indicating pollution,” Gratto continues. “I enjoy working with the students at UNCP and volunteers on the Waccamaw River to develop and implement the water quality monitoring program. Building relationships with our volunteers and partners is integral to recruitment and retention so the program can grow.”

Erin Donmoyer is the riverkeeper for the Black and Sampit Rivers, a watershed that covers 2,145 square miles and 160 river miles. The two rivers are very different systems both ecologically and in terms of their human impacts, so Donmoyer’s initiatives and priorities vary greatly.

On the Black River, the Alliance has the deed for 450 acres of land with river access that, combined with 200 acres owned by Georgetown County, forms Rocky Point Community Forest. This community forest is the last land stop along the state’s next proposed state park, the Black River Water Trail and Park Network.

“The strategic planning efforts around the greater River Trail and how Rocky Point will fit into the vision is an important part of my job,” says Donmoyer. “One of my priorities, as the planning goes into final stages, is ensuring the park system provides what the communities along its shores want and will find useful, as well as ensuring the park remains an asset to conservation of the Black River.”

Donmoyer adds that litter is a major issue along our rivers, particularly around some of the smaller rural towns along the Black River.

“Getting the public to appreciate, respect, and care for the river and its surrounding lands and swamps, as well as public education around the impacts of litter and illegal dumping, is another priority of mine,” Donmoyer says.

One method Donmoyer finds effective is getting the local communities involved in cleanups, both through simple visibility of the efforts (i.e. education around how much trash is collected, what kinds of trash, and how much labor it takes), and hands-on involvement from community members.

Donmoyer says one of her greatest concerns is the lack of freshwater wetland protections at the state level in South Carolina. Currently, no state regulations protect freshwater wetlands. Any protections that are in place are merely recommendations with no legal repercussions if individuals, developers, or companies choose not to adhere. Logging in swamps, forested floodplains, and river corridors is a primary focus.

“Bottomland hardwood forests and cypress-tupelo-gum swamps are quietly disappearing in the shadows,” Donmoyer continues. “Our swamps are an incredible ecological resource, home to scores of rare, threatened, and endangered plants and animals, as well as a mitigation for the increased intensity and occurrence of flooding that our region is experiencing. These swamp lands act as giant sponges for floodwaters and pollution. Their regrowth happens slowly, and not in a timeline that aligns with the rate of climate change. Our earth is changing, and we can’t rely on conditions to continue to be favorable for regeneration of forests. Our earth needs them today, tomorrow, and into the future.”

Donmoyer’s other river, the Sampit River, is unique in that it’s short—only nine miles long—but is saddled with a high amount of industry, factories and opportunities for pollution along its shores. It’s a river that begins in a blackwater tannic swamp system, and meanders through a patchwork of beautiful freshwater and brackish marsh systems that were historically rice fields. The system is going through ecological shifts, as salt water intrudes with sea level rise, land subsidence, and the average exposure to salinity increases. Arising from the marsh grass are relics of old cypress trees that used to rule the shores, but are intolerant to salt water.

Several factories along the shores of the Sampit have treated wastewater discharge/effluent input to the river or its tributaries. This discharged water is required to be tested by South Carolina Department of Health and Environmental Control (DHEC), but most information is self-reported, with minimal DHEC testing on site. The lack of monitoring, equipment failure, and human error pose risks to the cleanliness of the river, which is a small, delicate ecosystem.

Jeff Currie, riverkeeper for the Lumber River, echoes many of the concerns raised by Donmoyer and their other colleagues. He said pollution and runoff from industry and farms is a major threat to the health of the rivers and wetlands. Sporadic flooding caused by tropical storms and hurricanes only adds to the challenges.

With all the challenges and threats our watershed faces, it’s easy to see why the riverkeepers, volunteers and the entire Alliance team work so diligently on their mission. Population growth and business expansion in the region are just two of the more important factors affecting the health of our rivers and their accompanying swamps and wetlands, but the Winyah Rivers Alliance is staying vigilant to protect these valuable resources for generations to come.

Winyah River Alliance Board Members

Clay Swenson (President)-Small business owner

Reggie Daves (Vice President) - Retired physician/Waccamaw Audubon

Michelle Lewis (Treasurer)-Accountant, Black Scenic River Advisory Council

Amy Hill (Secretary) - Coastal Carolina University Scientist

Tom Badgett-Retired Dentist

Betty Gause-Horry County Parks and Recreation Program Coordinator /Director of James R. Frazier Community Center in Bucksport

Dan Hitchcock-Clemson University Scientist

Richard Moore-Retired Coastal Carolina University Professor/Waccamaw Audubon

Dana Shields-Federal Government Scientist

Martha Smith-Retired Administrator

James Vaught-Retired Optometrist

David Shane Lowry-Distinguished Fellow in Native American Studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology

To get involved with the Winyah River Alliance or to donate, contact the Winyah River Alliance at:

Winyah River Alliance

301 Allied Drive – 160C

Conway, SC 29526

Phone: (843) 349-4007

Website: winyahrivers.org