Out of tragedy comes new life for local man

By November 2021, Chuck Bell, of La Belle Amie Vineyard in North Myrtle Beach, had been in declining health for some five years. His diagnosis of the incurable lung disease pulmonary fibrosis was the cause. What began simply as a nagging, but chronic cough had progressed to something much more serious, and, he would later learn, was terminal. Up to this point, friends and regular customers at the popular North Strand Vineyard and music venue, knew, or at least suspected he had health issues. But even the 69-year-old Bell was unaware his remaining time on Earth was measurable in months, not years.

Two years later, Bell is happy, active, working and enjoying a second chance at life as the recipient of new lungs after a double lung transplant in April 2022. He credits the donor’s family that looked past their grief long enough to give a stranger this gift. He also credits the remarkable Pulmonary Transplant team at Duke University Medical Center, and the love and support of his wife, Vicki Weigle.

Bell experienced a very close call. Had he waited much longer to seek medical advice from Duke University Hospital, it might have been too late.

We spoke on a recent warm and sunny afternoon at the place the couple calls home, La Belle Amie Vineyard. The business was closed that day which meant the wildlife was happily surveying the heavily wooded grounds. A giant hawk swooped in and lit on a pine tree branch just 30-feet away. Countless squirrels foraged for anything edible while Starr, their sweet Lab-mix and Vineyard mascot, found a pleasant sunny spot to snooze not too far away from our conversation.

The candid discussion was both wonderful and suspenseful as he and Vicki recounted Bell’s journey from near-death to good health. The couple shared their thankfulness for a successful outcome and the extensive team of professionals at Duke who literally breathed new life into a patient who was dying.

“Before my first meeting at Duke I had finally prepared myself to accept the fact that it was all but over,” says Bell, who along with wife Vicki, La Belle Amie’s owner, are the insatiably social and friendly faces of the Vineyard. The couple recalls that as winter was settling over the Grand Strand in 2021, they had quietly and privately been preparing for Chuck’s passing. Both multi-generational residents of Horry County, “Chuck and Vicki” as they are so well known, soldiered on with Chuck’s condition worsening incrementally each day.

“I was gray,” recalls Bell, “and looked like I’d walked out of a morgue. I’d tried to hide how badly I felt, and didn’t talk about it much, but people knew. I couldn’t do much at all, limited walking, no lifting and no energy or stamina.”

But all hope wasn’t completely snuffed out quite yet.

“With the help of family members in Greensboro, N.C., I was able to see a pulmonologist there who referred me to Duke,” says Bell. “I had heard that Duke University Medical Center had a lung transplant program. Duke now accepts self-referrals, but at that time they didn’t. For years I had been under the misconception that I was too old for a lung transplant.”

January 2022

Bell had seen pulmonologist Dr. Ramaswamy affiliated with the Moses Cone Memorial Hospital in Greensboro N.C. in November. In mid-December Dr. Ramaswamy referred Bell to Duke. Immediately Duke scheduled an in-depth medical work up January 3-7 accessing Bell for the lung transplant program. At the time of their initial meeting at Duke, the couple were informed that Chuck might not live to see the end of summer.

“That hit me hard,” he recalls. “I knew I was seriously ill, but to have a team of doctors tell you that to your face is not easy.”

January 11, 2022

“I got a call from Cynthia Lawrence, my transplant coordinator,” says Bell. “She said, ‘You have been accepted into the program as a potential candidate.’ She was very careful to emphasize “potential,” with no guarantee of making the transplant list and of getting the transplant. A number of circumstances could change that might disqualify me, including being too sick to survive the transplant, or no suitable organs might be found or available in time. But the call was simply overwhelming. For the first time in years, I felt hope.”

“We only consider end-stage lung disease patients,” Dr. Katie Young says from her office in Durham, N.C., “and the earlier we see a patient, the better.” Dr. Young is the assistant professor with Duke University Lung Transplant and is Bell’s transplant pulmonologist. She is a part of the Duke lung transplant medical team that works closely with the surgical team, the patients and their families. She has been at Duke in this multidisciplinary role for three years.

“Vicki and I were so impressed with the excellent communication, professionalism and care we received at Duke, at every step of the way,” continues Bell.

Just what is pulmonary fibrosis?

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) is one of the many lung diseases which cause devastating damage to the lung tissue and has very few significant treatment options. It can be caused by smoking, exposure to asbestos, coal dust and other environmental triggers and even some medications list IPF as a possible side effect. It can also strike individuals with no known hazardous exposures. It is currently incurable, and its victims have an average remaining life span of three-to-five years from the point of diagnosis. Newer anti-fibrotic medicines can help incrementally, slowing the progression with mixed results. Some with acute IPF can die quickly and others with chronic IPF can live longer, but nobody survives this disease without a lung transplant, and not all pulmonologists will consider this option. Self-referral to a transplant center, and early in the disease, may be the best option for those with IPF.

“I’m with the team that assesses the patient to determine if they’re a good candidate,” Dr. Young says, “and if they are, then we’re tasked with optimizing them prior to surgery and sticking with them after surgery.”

According to the NIH (National Institute of Health) around 30,000 to 40,000 new cases of IPF are diagnosed annually in the U.S. and Duke is one of the leading transplant centers in the nation performing more than 100 lung transplants annually. Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia is ranked #1 for annual volume, just slightly higher than Duke, though Duke remains #1 for the most lung transplants performed overall, some 2,500 since 1992 when their program began. The Mayo Clinic, The Cleveland Clinic, St Joseph’s (Phoenix, AZ) and a handful of other transplant centers perform about 70 to 100 lung transplants annually.

A lung transplant in and of itself is no guarantee of full recovery, but in the case of end stage lung disease, such as IPF, it’s the only known way to offer the possibility of significantly improved quality of life. The median survivability after lung transplant is 5.8 years, according to the NIH, but some 35-percent are still living at 10 years, and some even longer. Howell Graham of Wilmington N.C. just recently died at 60 years old. He had held the record as the longest surviving double lung transplant recipient in history, having had his surgery in 1990 due to severe cystic fibrosis. He lived an excellent quality of life for some three decades after surgery.

Green Lights

February – March 2022

When Bell got the call from Cindy Lawrence, the transplant coordinator at Duke, and she told him ‘You’re approved for the program,’ Bell was just beginning to understand the process and pitfalls of being an organ transplant recipient. Though he was still not yet on the transplant list, he was officially enrolled. Then would come prehab, where Dr. Young’s team needed him to be as healthy as possible before going into surgery and for the team to have markers in place, a baseline to measure his deteriorating condition.

“We were told we’d be there for a minimum of three months, maybe longer,” says Bell. “We found a furnished apartment and signed a six-month lease. We were just five minutes away from the surgical center’s doors. Our staff at the Vineyard performed wonderfully, keeping us afloat while we were away.”

Pulmonary Rehabilitation lasts six weeks and takes place five days per week. It includes supervised interval training, physical workouts, resistance training, and a minimum of twenty minutes per day on the treadmill, not so easy when you’re on oxygen and your lungs are at a greatly diminished capacity. It also includes countless educational Zoom seminars covering nutrition, health safety awareness, new medications and the new life post-transplant.

“They measured my performance, like how far I could walk in six minutes, balance, strength training, all of which helps determine your successful recovery by building muscle strength and endurance,” continues Bell. “But it also gives them a baseline, so if you start to decline significantly during prehab, which I did in my last week, they’re aware of the deteriorating condition. I was on oxygen 24/7, declining in my treadmill ability and pushing an O2 tank on wheels. That helped move me up on the transplant list.”

After successful testing and grueling prehab, then and only then, was Bell told he’d be put on the transplant list. His ever-worsening condition helped bump him even higher on the organ allocation list.

April 4, 2022

“He had been on the waiting list for 10 days,” recalls Vicki Weigle, “and the call came in on the afternoon of April 4.”

3:00 p.m.

“I knew I was failing fast,” adds Bell. “I had weeks or maybe a month or two before I was done. Our apartment was on the second floor and it was taking me 10 minutes to get up those 18 steps. Cindy Lawerence, the Transplant Coordinator, was on the phone with us and said ‘Mr. Bell, are you ready for some new lungs? ‘I am so ready,’ I answered, and was told to come in at 10 p.m.”

9:55 p.m.

“By this point a possible donor has already been identified,” says Dr. Young, “and in Chuck’s case this had been around 3 p.m. Someone from our surgical team has flown or driven to the donor’s hospital to talk with the donor’s family.” [some specific information has been omitted to protect the donor’s anonymity].

Brain death or recent trauma leading to death are the primary circumstances leading to a donor’s family having to make the tough, heart wrenching decisions. The donor may have suffered a severe stroke, been in an automobile accident or undergone severe trauma of some sort, such as shooting, or even drug overdose. Bell had already agreed to accept lungs from a donor under virtually any circumstance; exposure to Hep C, HIV and even high-risk lifestyles, just grateful to have made the list at all.

Vicki drove her husband to the surgical center, around five minutes away, excitement mounting.

Was he fearful?

“Not really, no,” says Bell. “Yes, there was some anxiety, but mostly excitement and gratitude that I’d been given this chance.”

10:15 p.m.

Bell is prepped for surgery and waits in a room with Vicki.

“I remember looking back at my life and thinking about what an adventure it had been,” says Bell. “I wasn’t really worried or terribly nervous. I was eager to get it done and let the chips fall where they may. I knew the mortality rate coming out of the surgery was very, very low. My heart was strong. I knew I was going to wake up and see my Vicki.”

“I remember the wait from 10 p.m. until they wheeled him out,” recalls Vicki. “Chuck was in and out of it, partially because of the preanesthesia drugs, but I was wide awake.”

April 5, 2022 – Rebirthday

5:30 a.m.

Pre-operating preparations finished and the patient ready to go, Chuck is wheeled into the OR.

“At this point the donor lungs may not even be here,” says Dr. Young, “but they’re identified as a match, they’re on ice, and they’re on their way.”

“They told me to go home and rest,” says Vicki. “I loved the communication I received from Duke at every step of the way. They would text me and say ‘The patient has arrived in the OR,’ then another text would come a while later, ‘the procedure has started,’ ‘the procedure is ongoing’ – complete updates. They took him away at 5:30, and I expected the surgery to last 8 to 12 hours.”

(the following timetable is approximate)

6:05 a.m.

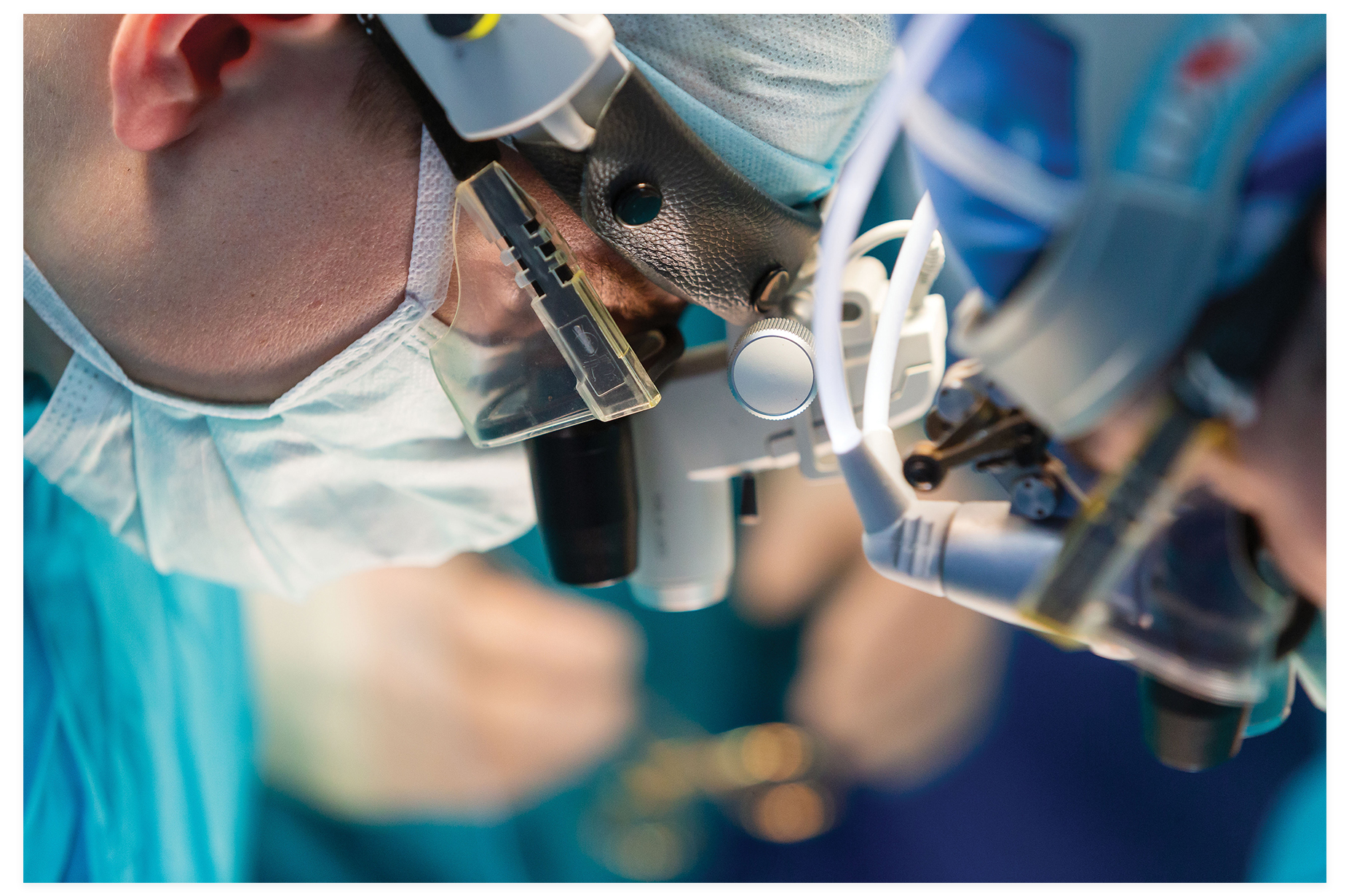

A team totaling up to six to eight surgeons, nurses, scrub techs, and anesthesiologists have assembled, and the first incision is made.

“It’s called a “clamshell incision,” says Dr. Young, who spared me the technical term ‘transverse thoracosternotomy.’ It goes almost from armpit to armpit and is the incision of choice of most lung transplant surgical teams. “Then comes the dissection of the old lungs [which Bell donated to research science] and that can be the most time-consuming part of the surgery, which can last a total of six to 24 hours.”

9:15 a.m.

With the old lungs out, remarkable machinery and the teams that operate it keep him alive.

“We use Cardiopulmonary Bypass or ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), which circulates the blood from the patient’s body, oxygenating it, then returning it to the body,” says Dr. Young. ECMO, developed in the 1950s, is essential for nearly all heart and lung operations, and is also used in critically ill Covid patients, greatly reducing mortality rates.

12:12 p.m.

“The new lungs are fit in one at a time,” Dr. Young continueds. “It’s very delicate work. This careful sewing reconnects blood vessels and the rest of the lung tissue. The same is done with the other lung.”

2:15 p.m.

“We take the patient off the bypass circuit, monitor their breathing, their O2 and CO2 levels, and if all looks good the surgical part of the transplant is over.”

3:00 p.m.

“I got a call,” says Vicki, “and looked at the I.D. It’s Dr. Haney (Chuck’s chief surgeon) from Duke. My first thought was ‘Oh no, something went wrong,’ but instead he told me the procedure went extremely well, the patient did really well, we’re finishing up in the next hour or so. He was so reassuring. He told me to come around 6 p.m. and Chuck will be in recovery.”

6:00 p.m.

“Chuck looked like a science experiment,” Vicki recalls. “He had 30 tubes going in and out of him and I don’t know how many machines were attached. And so many doctors and nurses attended to him. One Doctor came over—she was a pulmonologist/scientist—because Chuck had donated the old lungs for research, and she told me how grateful she was and how happy that he did so well. I asked her how often they were able to determine the exact cause of the IPF and she told me ‘Not very often, a low percentage of the time.’”

7:19 p.m.

With Bell still not awake, the team told Vicki to come back the next morning.

April 6 – 9:00 a.m.

“I got another call and panicked,” recalls Weigle, “but they said, ‘we moved your husband to another floor, Step Down from ICU, and have already had him up and walking this morning.’”

“I hurt everywhere,” says Bell. “I was in a lot of pain, which is to be expected. I was told I needed to do a minimum of 16 laps around the hospital corridor before they’d ultimately discharge me. I was only required to walk one lap that first morning, so I did two. I was getting stronger every day, walking more laps until I was released eight days later, a total of 10 days in the hospital.”

April 14 – 9:51 a.m.

Released from the hospital and driven back to the apartment by Vicki, Chuck was feeling better than he had in years.

“I took on those 18 steps at the apartment like they were nothing. The last time I’d gone up them took me nearly 10 minutes. I’ll never forget getting to the top. I don’t remember any pain or soreness, only elation. At the top of the stairs, I took a big breath, and felt such gratitude for everything and everyone along the way.”

Not able to return home yet, Bell still had six weeks of pulmonary rehab and physical therapy, before he was cleared to leave Durham permanently.

“Average hospitalization after transplant is about three weeks,” says Dr. Young. “At 10 days, Chuck had a remarkable course without early on complications. Lung transplant was the right option for Chuck and he would have never met us had he not asked the question ‘Am I a candidate for lung transplant?’”

“Not every state has a lung transplant center,” Dr. Young continues, “and we are adept at meeting with out of state patients. We can do video consultations for those who are very far away and make those initial introductions. Patients are now able to self-refer and our team will reach out to their local pulmonologists to get records as they’re available.”

“On my first trip back to the Vineyard, two months after the surgery, everyone remarked about my energy level and at how well and healthy I looked,” says Bell. “If I acted like I felt great, it was because I did feel great, and I do feel great. This transplant is not just about extending your life for a couple of years or even a decade, it’s about the quality of life. I now walk 5 to 7 miles a day. Before the surgery my 6-year-old grandson wanted me to walk upstairs to see his bedroom and I couldn’t do it. Now I can race him up the stairs. On a recent visit I helped carry his bunk beds up the stairs and assembled them. Living, not just existing, that’s what really matters.”

The future?

Chronic organ rejection is the number one killer for organ transplant patients, but the numbers don’t always mean everything.

“I tell my patients the [mortality] numbers after transplant are just averages,” says Dr. Young. “Many will outlive those averages.”

Bell is required to be on immunosuppressive medications to combat organ rejection, and others to combat infection, and will be for his lifetime. He says he considers this a small inconvenience for the new life he’s been given.

“Right now, I’m enjoying this rebirth,” says Bell. “Vicki and I so want all to know that there are potential options for whatever healthcare issue they may be going through. We all have to be our own healthcare advocates, take responsibility for our lifestyle choices, and with serious health conditions get second and third opinions. It’s worth the effort. Never be afraid to look outside of the box for answers. That’s where I found hope.”

For more information on the Duke Lung Transplant Program and how you can self-refer, visit:

https://www.dukehealth.org/treatments/transplant-program/lung-transplant or call 919-613-7777.