One Year After Helene

With the windows wide open, we wake to birdsong from just outside our tiny A-frame cabin overlooking the French Broad River in Asheville. I slip on sandals and follow a gravel path edged with blooming lavender that winds past several other cabins to the Wrong Way River Lodge, where a barista is making morning coffees and teas to order. A little later, I hear happy shouts and laughter through the trees—there’s about a dozen people in pink inner tubes floating by on the water. This all feels hopeful and brightening.

After seeing video clips of the terrifying flooding last September, we weren’t sure what to expect when we booked a two-night stay at this urban-outdoorsy lodge within three miles of downtown Asheville—and just across the road from the French Broad River, one of the primary waterways to swell and spill over during Hurricane Helene.

Photographer Peter Frank Edwards and I had made the drive to Asheville the day before, heading about four hours northwest of Charleston, gaining elevation and mountain views in the final stretch. I’ve always considered Asheville (elevation 2,200 feet) to be snugly cradled by the ancient peaks of the Blue Ridge Mountains—a safe getaway from our coastal storms. But last year, the force of tropical wind and rain moved inland. Zipping north from Florida as a Category 4 at landfall, Helene was a record-breaker. September 26 and 27 mark the one-year anniversary of the devastating storm that brought catastrophic flooding to parts of Western North Carolina, including Asheville. The French Broad River rose fast and furiously into the floodplain, peaking at a whopping 24.67 feet. (For context, the flood stage for the river is nine feet.)

“You can’t imagine how much water there was. It was otherworldly,” recalls Wrong Way River Lodge & Cabins co-owner Shelton Steele about the torrents created by the fusion of floodwaters from the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers. He and I are talking in the lodge’s canteen, where there’s a cool collection of local products in the adjacent shop, including bars of French Broad Chocolate, tins of Spicewalla chai, and satchels from Twin Denim Co., along with a fridge full of local and regional craft beers.

A former river guide, Steele cofounded Wrong Way in 2022 to bring visitors closer to Asheville’s outdoor experiences. The 16 A-frame cabins, towering above the roadway, are well-elevated to help protect from floodwaters, and that foresight saved the property, which reopened a few months after the storm. Steele says the entire city, especially what’s closest to the river, is in a reset mode, with many decisions yet to be made about what will be rebuilt and where. Meanwhile, he’s very thankful for the visitors who are returning. “It’s a really warm moment to visit Asheville.”

We find an infusion of that warmth when we meet local friends at Chai Pani. The downtown restaurant is one of their favorites, they tell us, smiling as we open the door and see the kaleidoscope of color inside. Founded in 2009 by India-born chef Meherwan Irani and his wife, Molly, Chai Pani is a tribute to Indian street food, its menu replete with hot naan bread, spinach saag paneer with tomatoes and chilies, and simple but glorious pappadams—lentil crackers so thin they melt on your tongue. Nearly every table is filled, and conversation buzzes as we’re seated in the cushiony curve of a turquoise and red banquette. Chandeliers overhead are arrayed in pink flowers, tassels, and marigold-colored pompons; and a mural of oversized florals adorns one of the brick walls. In a tucked-away bar space upstairs, a glowing pink neon sign spells out “Indian Food.”

Seated near our table are several families with children, and it feels like a local crowd. Chai Pani has a strong community presence. It had the rare luck of retaining electrical power after the storm, and the nonprofit World Central Kitchen helped find resources to restore its water service quickly. Meherwan, Molly, and the restaurant’s team immediately jumped in to help, cooking and distributing more than 25,000 meals to those in need.

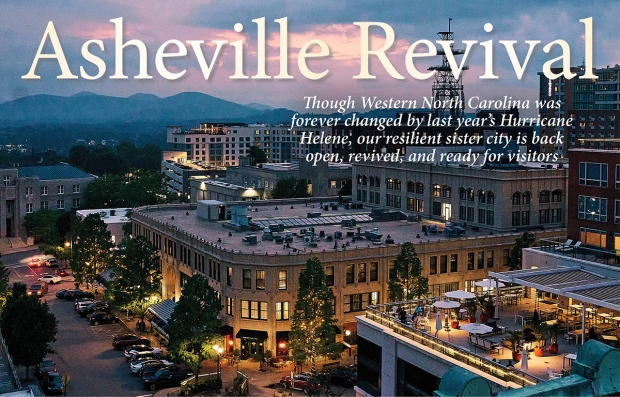

Next, we head to the century-old Flat Iron building that opened as the Flat Iron Hotel in May 2024 to great buzz after extensive renovations. It has a stylish ground-floor restaurant, Luminosa; a cool basement speakeasy; and a rooftop bar. We arrive near sunset and immediately take the elevator to the ninth floor. There’s a central indoor space that opens to three outdoor lounge areas, and we step outside to feel cool air blowing in from the mountains—it’s a great vantage point over the city streets. Though tourism numbers have shown a drop in visitors and hotel bookings in Western North Carolina since the storm, this wedge-shaped hotel and the immediate neighborhood feel vital, even outright lively.

The feeling is confirmed when we take the elevator back down to the street—Luminosa is brimming with guests at tables inside and lining the sidewalk. Less than a block away, we hear music. It’s swing-y like old Django Reinhardt, except with a stand-up bass in the three-piece band. Storefront windows give views to the new corner venue, Fitz and the Wolfe (a nod to Zelda Fitzgerald and writer Thomas Wolfe). The double doors are wide open, the dance floor full. We stand in the doorway, pulled in by the sound, and take in the timeless scene—particularly a man in a white T-shirt and a woman in a pale peach dress, who are dancing with great energy and finesse. Music and smiles fill the room.

The next day, we return to the riverfront, first to bike along its banks and into the River Arts District. We brought our own bikes and pedaled out from Wrong Way to pick up the French Broad River Greenway trail just across the road. While a few sections are still closed due to storm damage—the Greenway literally drops off into the river at one point—the trail has a steady stream of bicyclists, runners, and people walking. The biggest crowd we encountered was on the lawns and paths around the riverside New Belgium Brewing (I was curious to stop by after seeing signs for the “Liquid Station.”) The large, modern brewery offers tours and hosts food trucks, and its grassy setting resembles a lawn party.

Nearby at the Craven Street Bridge Boating Access Area, where wildflowers bloom in rain gardens along the bank, we catch up with Anna Alsobrook, who heads the French Broad Riverkeeper. She had just finished a 140-mile, 10-day group camping trip to assess the river’s condition post-storm, since the recent cleanup of debris by the Army Corps of Engineers, and says it looked a lot better than she had expected. “From a recreation standpoint, the river is open.”

Recounting having paddled sections in a kayak, canoe, and stand-up paddleboard, Alsobrook says she saw people back on the water fishing and boating. She recognizes that some river outfitters may not yet be at full capacity due to equipment lost in the storm or difficulties restaffing but also sees progress. “We want people to come back.”

I have fond memories of visiting galleries and studios and sipping beer in the sunshine at the Wedge in past visits to Asheville’s River Arts District—often called “RAD” these days. Along the French Broad River, the buildings and warehouses of past factories and industry had transitioned into a cool conclave for painters, weavers, carvers, jewelry designers, sewers, and other makers and artists of all stripes.

These days, the landscape here shows some of the starkest reminders of Helene. Michael Hofman, who operates Hofman Studios on Roberts Street, says his studio was spared severe damage because of its elevation—it’s farther from the river in what’s now called “Upper RAD.” When we stop by to see the textured porcelain pieces that Hofman crafts by imprinting them with lace patterns and other materials, he pulls out the 2024 RAD map and rips it cleanly in half. “This part is gone,” he says of the sections on Lyman Street and Riverside Drive.

A few doors away is a hotel that hadn’t been open a full year when Hurricane Helene struck, but it survived and fully reopened in January. The Radical, an exposed brick and graffiti art revamp of a 1920s-era warehouse and former cereal factory, was abandoned for years and sometimes used for paintball games. “I’ve heard people say they came here for raves in the ’90s,” says Nikki Stewart, the hotel’s director of sales.

I peek into a couple of The Radical’s rooms; they have the cool vibe of an urban loft. Its Golden Hour restaurant has soaring windows and an industrial-elegant feel with polished concrete floors, brown leather upholstered chairs, and brick walls painted charcoal-black. Speaking of coal, much of the cooking here is over a wood fire. Chef de cuisine Kevin Chrisman brings out beautifully plated dishes, including a delicious sheepshead fish with a buttery tarragon sauce served over a bed of radishes, turnips, and greens.

Atop The Radical is a spacious, covered bar and open-air lounge with extraordinary views across the French Broad River toward New Belgium Brewing and a slew of inventive seasonal cocktails. The day we visited, the crew was making Thai basil gimlets with absinthe and a Prosecco and strawberry concoction called “Picnic in Pink” that proved to be an easy drinker in the sunshine.

I realize that I’ve been enjoying a sunny, beautiful, and dry day in Asheville. I wonder what Stewart and others who experienced the storm and aftermath are still feeling. This is new territory for everyone. The river crossed the railroad tracks, Stewart explains,“and no one had ever seen that before.”

As the city reaches its one-year anniversary of Hurricane Helene, it’s so good to see that the revival is on and visitors are warmly welcomed. More bright and hopeful mornings of birdsong are surely ahead.