A day in the life of Randy Clifton, STEM Educator

Forestbrook Middle School was once one of the largest in the Horry County School district, with around 1,400 students. Even after reducing its enrollment when new area middle schools opened, it still has some 900 students in the sixth, seventh and the eighth grades. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) educator Randy Clifton sees most of these kids in one of three STEM electives programs he teaches throughout the students’ academic career while at Forestbrook. Though teaching is his new-found passion (he started teaching just six years ago), he also exercises a creative bent that keeps him active as a performing musician.

His teaching day starts early and ends early enough for his moonlighting job, performing solo, two to four times per week around the Grand Strand, armed with a bucket of cover tunes and an acoustic guitar. I was able to spend a good part of the day watching Clifton in action at Forestbrook and found myself thoroughly impressed by his rapport with the students and astounded by the complexity of the coursework: App Creators (computer coding), 3D Design & Modeling, and a Medical Detectives forensic study unit.

Though we didn’t meet until just after lunch, here’s how a typical day starts and ends, and what I witnessed in the middle.

7:45 a.m.

Clifton clocks in each day, Monday to Friday, at 7:45 a.m. However, he doesn’t see his first students, seventh graders, until 8:20. His two back-to-back groups of students take the Medical Detectives course, which is a kind of forensic case study-styled class where the kids get to dissect sheep brains while learning about the body’s many systems.

8:25 a.m.

Not unlike herding cats, Clifton manages to get all his kids in the classroom and settled, but not before lots of conversation, laughing, and finally quiet to start the class. A ceiling-mounted projector blasts a color image on the screen, while each kid settles in, nose in their own device; a laptop is provided by for the school for a small fee.

“I love this stuff,” says Clifton, who is 48. “I’m a total geek. When they offered me this job I thought, ‘I’m going to get paid to do this?’”

Unlike core curriculum classes (readin,’ writin,’ and ’rithmatic), where the teachers are required to have specific core education teaching undergraduate degrees and state certification, the STEM courses require the teacher to have a BA in almost any major, and then pass certification for the particular elective they hope to teach.

Part of the P.A.C.E. (Professional Acknowledgement for Continuing Education) program, this model alternative education process teaches smart and willing individuals, such as Clifton, arming them with the right skillsets, matching their personality, patience and brains to handle the many facets of public education.

Not everyone is cut out to teach, especially teaching cutting-edge curriculum. There are no shortcuts, nor is the STEM program an easy way to get into teaching. The demands and accountability are every bit as stringent for these STEM alternative educators as they are for their core curriculum counterparts.

“This curriculum comes through Project Lead the Way,” says Clifton, “so in order to teach any class I have to be certified, which means I have to go through the whole curriculum like the kids do, and prove proficiency, except I do it in a one-week intensive course. It can be daunting.

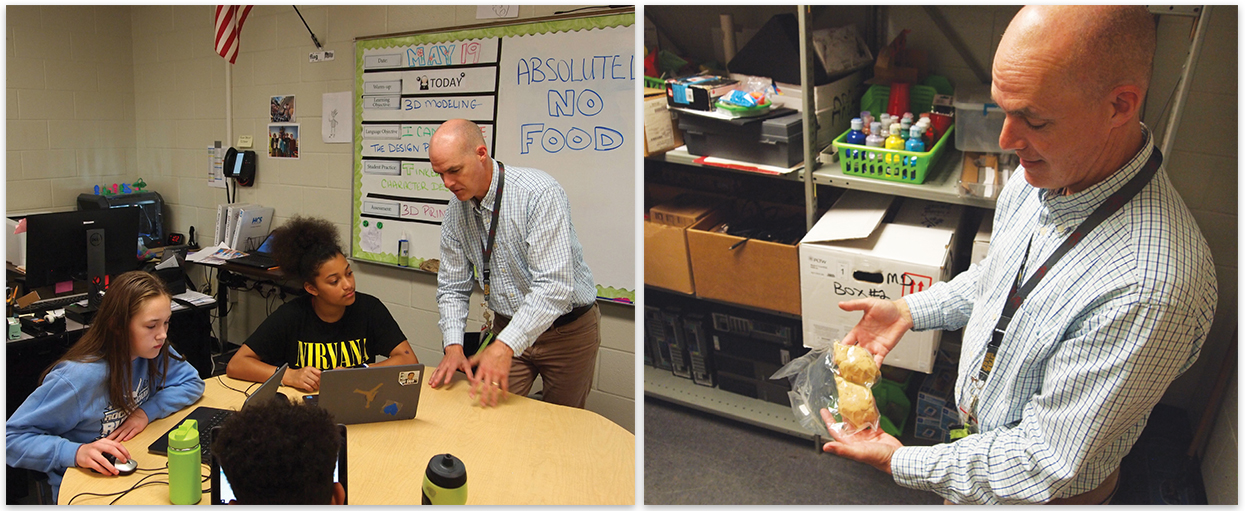

“In Medical Detectives we learn about the nervous system, for example. A lot of it is learning to infer through hands-on diagnostics. Our seventh graders love the labs,” he says. “The sheep brain dissection is a big selling point. The sheep brain represents a hypothetical case file of a human, and as we study this case file, the students must develop analysis skills to figure out what’s going on. Depending on the diagnosis, they must determine what part of the brain they might have to isolate and search. Some of these brains actually have tumors in them, and finding these tumors is part of the course work.

“My first year teaching a Lead the Way program was in General Design to all three grades,” continues Clifton. “It was a big success—the kids loved it. Then [our principal] said, ‘Let’s add Medical Detectives,’ so I took the courses and became certified for that. The kids also do a toxicology lab, where they test for [various] neurotoxins.”

In this way, Clifton explains, that a student in the seventh grade is exposed, for the first time, to medical forensics, and in high school may decide to follow an academic path toward the medical field or law enforcement.

“It’s important to find out what you love as early as possible, and just as important to find out what you don’t love. That’s a big part of what we’re doing,” says Clifton.

10:08 a.m.

Clifton’s second batch of 7th graders have filed out and he has a few moments to prepare for the next group, 6th graders, and grab a coffee (or in his case, a Mountain Dew).

11:25 a.m.

The next class of kids, 11-12 years old, file in, a delightful mix of personalities, sizes (some are tiny, and some are approaching six feet tall) and they take their seats, four or five to a table. They all fire up their laptops and look over the assignments for the day.

These future design engineers and architects have signed up for Design & Model, a 3-D graphics module, where kids learn the basics, including C.A.D. (Computer Assisted Design).

“They will start with basic shapes, learn to manipulate them, and create actual 3-D designs,” explains Clifton.

A large 3-D printing machine sits in the corner of the classroom. The fruits of these hi-tech machines, their labor and programming are scattered around the room. Small plastic toys, some with intricate, chain-like structures, were designed by the kids, fed into the machines, and created one layer of hot plastic at a time as the wide-eyed students watched in amazement.

1:08 p.m.

Clifton’s second group of sixth graders have left for their late lunch break, while Clifton does the same. He’ll only get 30 minutes before the next rowdy bunch of eighth graders file in for App Creators, a computer coding class in which Clifton has found an especially fun and creative way to engage the students.

1:35 p.m.

The oldest kids in the school, 13- to 14-year-old eighth graders, are a different breed altogether. They are becoming young adults whose brains are tested to the limit, especially in this particularly challenging class. Clifton has known most of these 8th graders since they were in the 6th grade, and the familiarity between student and teacher shows.

“I literally get to watch them grow up,” remarks Clifton, who is himself a father of four boys. His wife teaches at Forestbrook Elementary School.

“My wife and I are both originally from upstate New York,” says Clifton. “We moved to Myrtle Beach from Houston, [TX] in 2012. I did corporate marketing for many years, but didn’t love it. I saw this opportunity and plugged in about six years ago.”

The couple live in Socastee and have helped their own boys, now 14, 17, 20 and 21, navigate the public school system. The oldest has just graduated from Clemson University and is about to embark on a career of his own.

“The last female born on my side of the family was in 1906,” Clifton remarks with a grin. “My wife teases me and says if she’d known that she’d never have married me. She, of course, loves them all, but had a fantasy about a mother/daughter relationship like she has with her own mother.”

The Cliftons seem to possess that somewhat rare, ideal mix for teaching careers, understanding both the parents’ and teachers’ perspectives from real world experience. He feels that waiting to start his teaching career, for him, made real sense.

“When I was a younger man,” says Clifton, “I didn’t have the patience or personality to do this job, but now I love it.”

About changing careers, teaching older kids, and making more money, Clifton is now content, and has bloomed where he’s been planted.

“I thought about a [core education degree] or getting a master’s and teaching at a high school or college level, but I really love this age group,” says Clifton, who seems to have the perfect disposition for the job.

The students seem to adore him and he them. There’s fun and minor chaos (as you’d expect from middle schoolers) but only to a point. Clifton is in complete control, even if on occasion it appears he’s not. He speaks their language, corrects misbehaviors, knows the individual personalities of the students and relates to them in a way you’d hope every teacher might relate to and teach your own kids. He also has a sharp, piercing, immediate attention-getting whistle that could probably travel for miles. He reminds them to abide by the rules of his classroom, and for the most part, they do. He’s funny and they appreciate it.

In addition to the lessons on the curriculum, there are many lessons that Clifton much teach, both inside and out of the classroom.

“We’ve had leaders of local businesses come in and the one thing that comes up again and again is they complain about a lack of soft skills they see in young people entering the workforce: eye contact, shaking hands, conversations–the basic things that surround relationship-building outside of their phones.”

1:42 p.m.

Each class starts with a “warmup,” a few simple, course study-related questions that might require an Internet search.

“The warmup acts as a chance to settle in, get their brains acclimated, and then we get into the lesson of the day,” says Clifton.

“I expect you to abide by all the normal classroom rules,” he reminds the kids as the noise level grows.

“You know I can’t,” whines one student playfully.

“Yes, you can,” Clifton reminds him. “I have all the faith in you.”

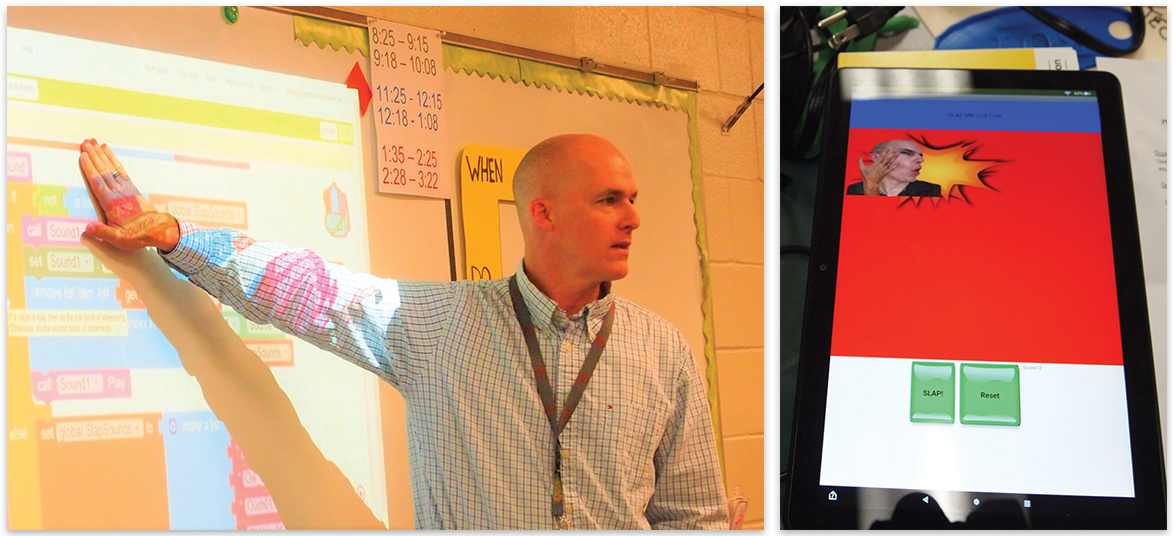

“Eighth grade coding is a love or hate thing,” says Clifton. “It can be a challenge to motivate those kids, but one of the ways we can do that is with something they like. So, in this class we actually design and create original apps they can put on their phones. The one we’re doing now is called ‘The Slap App.’”

Clifton’s kids have taken a head shot photo of their teacher, added in a floating, open-palmed hand, which, with the tap of a button on the screens of their phones, will slap Clifton in the face, complete with sound effects. Naturally, the kids love this.

“I remember when we first started designing the Slap App, I had an early version of it up on the big screen while we tested the slapping feature and sound effects, just as one of the administrators walked in,” he says. “He gave me that look like ‘What the heck is going on?’ and I responded with a, ‘please trust me on this,’” and the Slap App was born.

“This is not just dry coding–a big incentive for the kids is that once we’ve created the app,’ he continues. “they can test it and download it to their device and see how it actually works.”

2:25 p.m.

With class over, we take a moment to meet with Forestbrook Middle School Principal Melissa Rutenberg in the hallway near the cafeteria. Various kids passing by say “hi,” and she responds warmly in a mothering tone, asking how their day is going.

“We love Mr. Clifton,” says Principal Rutenberg. “He does a fabulous job with his students, and there’s a waiting list of kids wanting to take his classes.”

3:22 p.m.

Clifton’s final class for the day ends with the ringing of the bell. Occasionally, when he’s on “car duty” outside, he stays a bit longer, but on this day, he’ll leave right around 3:45 p.m. and head straight to his 5 p.m. gig at RipTydz in Myrtle Beach.

“I do three to four shows a week–The Tin Roof, RipTydz, Tavern in Surfside, and a few other places. I try not to overdo it, but I really enjoy performing.”

Summer break runs through August 4, and then the teaching starts afresh with a new batch of eager sixth graders beginning their middle school careers. At the start of a new school year, he says he will miss his current eighth graders, who have moved on to high school, and will likely remark that his former seventh graders have all gotten taller over the summer.

“Randy will have a child that’s 11 when they start, and 14 when they leave,” says Rutenberg. “We all notice a lot of change in those three years.”

The challenge of teaching really smart tweens and teens comes with a lot of testing, according to Clifton, academically and otherwise.

“They’re coming out of their shells, they’re getting social, gaining independence. I had no clue what to expect when I started. Working in technology, I find I’m only getting older and I’m getting further and further away from beating these kids at their own game. It’s hilarious to see what goes on sometimes. They try to pull things over on me occasionally, but I just have to laugh.”