Before we’d even signed the mortgage and been handed the keys, we’d already named our first house. The act itself, though premature, seemed to verify that, yes, we really were about to own a home and that, yes, in keeping with a coastal tradition—even for a house not on the beachfront—we had the right name it.

To name something is to know it, to own it, to be responsible for it. It is the oldest of acts. Take a look at Genesis. What is one of the first powers that God grants Adam? The power of naming the animals: “and whatsoever Adam called every living creature, that was the name thereof.”

Naming often consumes people as they rack their brains over how best to name their babies, their pets, their boats, their homes, even their cars. I myself am weirdly obsessed with naming—a genetic trait. One of the ways my family and I pass the time is to name the racehorses and yachts and companies we dream of owning, the products we dream of creating. My wife and I even invented a people-watching game called “Spot On,” in which we guess the names of passersby on the beach.

Suddenly finding ourselves with these new poetic powers, we surveyed the options. House names around here tend to be either straightforward and alliterative (e.g. “The Hensel House”), invitingly coastal (e.g. “Hensel Inlet Haven”), inside-jokish (e.g. “Halehe”—made from the first two letters of our names), historical (e.g. “The Gray Man”), animalistic (e.g. “The Blue Heron’s Nest”), or some combination of all of these.

“It’ll come to us at the right time,” we kept telling ourselves. “It’ll dawn on us.” (“Dawn on Us?” Hmmm. Not bad.)

Our housing search, by most standards, had been fairly quick. One of the great things about Murrells Inlet is its eclecticism—you’ll have a million-dollar mansion towering above its next-door neighbor, a singlewide trailer. You have new homes going up daily, and you have old fishing shacks that remind you of how seafood restaurants began in residential kitchens—hence names like The Fish House, The Crab House, The Oyster House, The Clam House.

We knew we wanted something old, something that had a story. I’d grown up in an old house, built in the 1920s, and more than anything I love the stories that come with old houses. Not just stories about the history of the house itself and its architecture, but the stories that take place over the years in each room. Houses, you might say, are the primary structures wherein we act out the dramas of our lives.

The house we found was an old Surfside Beach beach house built in 1950 and moved in 2000 to the heart of Murrells Inlet, in the Macklen community behind the Crooked Floor Tavern. Wide-porched, white-shingled, black-shuttered, wood-floored, all with a sense of history—we were in love.

Our real estate agent, Whitney Yonce-Hills—who has a deep sense of, and love for, Murrells Inlet history herself—told us that her fellow realtor, Randy Harrison, had actually grown up in the house.

Of their family history, the Harrison Realty Company website explains, “In 1956 the Harrison family became the 6th permanent family to reside in Surfside Beach. From the annals of city hall where the venerable Thomas Jenkins Harrison Sr. presided as the first mayor of Surfside Beach, to the present day, the Harrison family has been instrumental in Surfside Beach’s growth from a sleepy little seaside village to an incorporated residential community which has in turn become a highly desirable tourist destination.”

And so it dawned on us. The Old Mayor’s House. Yes, by God, that was it.

“The Old Mayor’s House” makes a nodding gesture to the history of the people who built and lived in this house; it makes a fun pun on the song “The Old Gray Mare” (“she ain’t what she used to be!”); and, to us at least, it seems very dignified and Southern—the name for the kind of place where anyone is welcome to come by and sit on our porch for a spell.

So we had a name. But then, of course, we needed somewhere to announce that name to the world. We needed a sign.

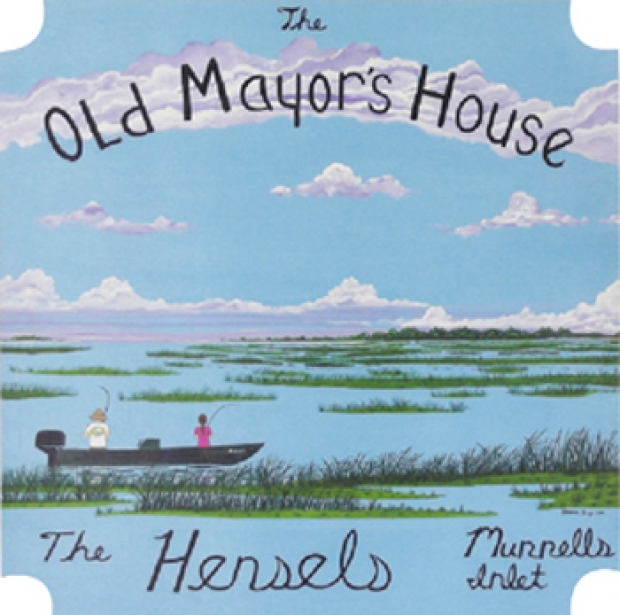

As destiny would have it, my oldest friend in Murrells Inlet is a muralist and a sign painter named Shane Gage. You may have seen a Shane Gage mural in a number of local watering holes—The Hot Fish Club, On the Half Shell, Jackson’s Bar and Grill. His paintings are always “marshscapes”—the view you get when looking out to the watery east, often at the “golden hour” when the sun touches its last rays across the creek.

Usually these paintings cover a wall over a pool table or a jukebox and are full of natural tones that brighten up the place and remind us of the beauty outside.

“I’ve painted Drunken Jack Island so many times I can do it with my eyes closed,” Shane has told me more than once. And so when it came time for a sign, that’s what we had to have—one of Shane Gage’s marshscapes with “The Old Mayor’s House” in arched lettering at the top and “The Hensels” and “Murrells Inlet” scripted below.

I watched as he sketched the first design in pencil on the back of a cardboard Budweiser box. Then he took out a piece of paper and made an even more intricate design, drawing the contours by memory, even the jetties and the johnboat in the foreground.

At last, he got out his brushes and paints and set to work, painting the clouds and blue sky and the johnboat with my wife and I in it. It was perfect, and we hung our marshscape beside our front door, hoping that one day—maybe in 2050 when the house is 100 years old—someone might ask us about it. And we’ll have a story to tell.