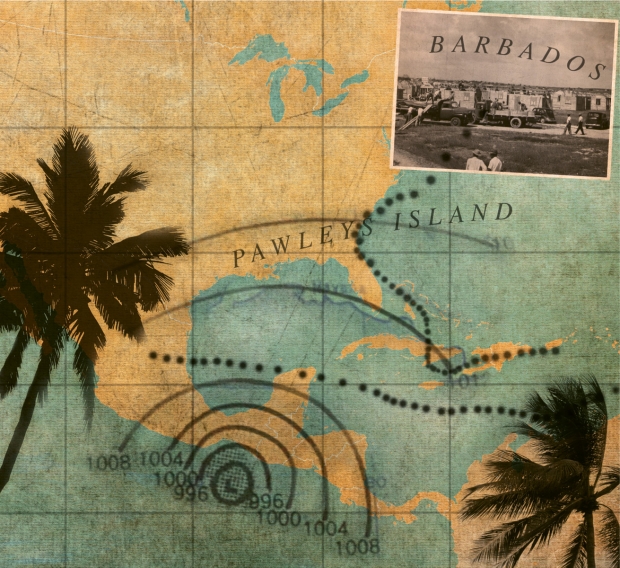

Experiencing a hurricane’s wrath—from Barbados to Pawleys Island

“To stay or not to stay” dominated our conversation as my wife and I watched the near-constant TV reports. Hurricane Matthew was moving up the East Coast. But the storm’s movement had been slow and erratic. Nobody knew its precise path. Mother Nature would make that call.

Even as Matthew approached Pawleys Island, our indecision continued. No evacuation order had been issued for folks on our side of U.S. 17. Dawn and I rolled the dice. We would “ride it out.”

Matthew arrived with fierce winds that spewed rain as if from some cosmic pressure washer. As I looked through the windows, the sight of whipping palm fronds carried me back to a long-ago time and place.

I was 12 years old, living with my family on Barbados. One September morning, the island’s radio station interrupted Beethoven’s Fifth with a somber announcement. A hurricane had formed out in the Atlantic. “Janet,” they’d named her. And Barbados was in her path.

My parents gathered up flashlights, candles and matches. Dad poured water into jugs while Mother checked the pantry. They tried to prepare my little brother, sister and me for the unknown.

The early afternoon air turned different. Hyperactive, just like me. I paced aimlessly from room to room. As the day got older, the wind changed from whistling to howling. Rain started and the wind threw that rain against the windows like a delinquent teenager hurling gravel at our house.

A loud bang dropped from the ceiling. Our eyes jerked roofward, expecting to see a jagged hole, feel water and destruction tumbling towards us. But that didn’t happen.

The sky became night-dark. Winds screamed, the roof creaked, windows and doors rattled. Water seeped in across the thresholds. The power failed, silencing the radio and the telephone. We were on our own now. Just us and Janet.

Daylight dawned a heavy-aired gray. Our house had held strong. We’d survived, at least physically. Even so, there was a certain emotional aftermath that hung around like the stale smoke which lingers after the fire has been extinguished.

We ventured outside. Small sections of our roof were missing. Banana tree leaves, sticks and other debris were strewn everywhere. Across the street an old house sat cattywampus on its foundation. One outside wall was bowed out. The opposite one bowed in as if the big bad wolf had huffed and puffed himself breathless. Nail-pierced pieces of lumber lay scattered about like oversized Pick-Up-Sticks.

Up and down the street, neighbors checked on each other. Miraculously, nobody near us had been seriously injured.

By the following day, many of the roads had been cleared enough so we could drive around much of the island. We headed for nearby Christ Church Parish. My father stopped the car in front of what was left of a fortress-like church. Now the end walls were gone, as was the roof. Villagers stood among the rubble, gesturing, weeping. I climbed over splintered benches, stepping on stones splotched with blood gone brown. A piece of fabric marked the spot where a woman had tried to flee. But the exploding walls had stopped her escape, her screams and her pulse. The same fate had befallen eight other locals. Nausea engulfed me like a suffocating pall.

We continued our drive in somber silence. Devastation covered the countryside. Sugar cane plantations were wiped out, along with the livelihoods of planters and machete-wielding harvesters. Wherever we went, houses had been torn wide open, spilling their insides as if disemboweled by some supernatural cannibal. In village after village, people milled about, stuck in a state of shock, mourning what had been and what might never be again. An old woman sat on her haunches atop the wreckage that was once her home. She stared into the distance. Grief ran all wet-streaked down her dark face and onto what was left of her tattered dress.

When the power returned, the radio told us Janet had killed at least 35 islanders and left 20,000 homeless. A U.S. Navy hurricane hunter airplane had flown into Janet’s eye, never to emerge. Gone without a trace.

Janet had done her best to wipe this small spot of land off the face of the earth. Now the survivors set about the business of cleaning up and rebuilding what could be rebuilt, including hopes and dreams.

Back in Pawleys Island, Matthew’s wind and rain subsided. An eerie kind of still told us we were in the hurricane’s eye. Suddenly the backside of the storm barreled in from the west, stronger than ever. Branches of backyard trees slapped across the panes of an attic window. Toppling pines around us sounded like a marauding herd of elephants. Visions of Janet flashed through my mind.

Our lights flickered a couple of times before the power died. We were on our own now. Just us and Matthew.

Tall piles of roadside debris have disappeared now. Sand-buried streets on Pawleys Island have been cleared. Full recovery, however, will be a long time coming … if ever. As for me, indelible images persist of the time and place where Matthew met Janet. At least in my mind.

COLLAGE BY MOLLY WICKHAM