The advent of Brookgreen Gardens was not man’s first effort to impose his will on the wild marshes of the Waccamaw neck. Far from it. But how one of the most comprehensive collections of American sculptural art came to be here exists as an enduring tale of Southern aristocracy—one that goes back several centuries and encompasses the travails and triumphs of privileged families who made, lost, and regained their fortunes along these marshy Murrells Inlet banks.

Fauns and horsemen frolic under these stately moss-draped oaks. Hoofs and chins raised skyward, they never tire; their visage is always fresh. Less virginal than the views at Brookgreen Gardens, however, is the story of how these figures came to live here, among the artfully constructed vistas and manicured lawns created by Archer and Anna Hyatt Huntington—a New York philanthropist and his sculptor wife. Together, they turned these more than 9,100 acres into an artistic showcase and a natural refuge that opened its gates in 1932.

Centuries before this spot became a public respite, however, the land existed as a private sanctuary for several South Carolina families who owned the four plantations amassed to comprise Brookgreen.

Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the South’s most valuable properties were controlled by men—wise and foolish, proud and unsure, educated and not—who at times even married cousins in an attempt to maintain their estates. The properties that make up Brookgreen Gardens were no exception. Immigrants to the Carolinas first laid claim to this rich land along the Waccamaw River in 1711, and, with their African and Indian slaves, developed it into large rice plantations along the marsh.

Named The Oaks, Brookgreen, Laurel Hill, and Springfield, these four plantations were also family homesteads, and, as such, they became the setting for tales of intrigue, ambition, fortune, and, at times, scandal. Each one has a history and a story, distinctly Southern—whispered among the shadowy forms that stand beneath these trees.

The Oaks Plantation, pre-Brookgreen.

Joseph and Theodosia Alston of The Oaks plantation faced tragedy at nearly every turn in their lives. Precocious children of ambitious parents, Joseph and Theodosia seemed destined for wealth, intellectual attainment, and political success.

Joseph Alston was a wealthy man among wealthy men. Educated at the College of Charleston and Princeton, young Alston met and fell “passionately in love” with Theodosia Burr, the brilliant, beautiful daughter of Aaron Burr of New York. Her ambitious father channeled all his efforts into developing the perfect female equivalent of himself, and, by age ten, Theodosia was an accomplished linguist, though her father pushed her to excel in all endeavors.

Aaron, a political force in his native New York, was best known for seeking (and almost winning) the presidency of the United States at the dawn of the nineteenth century. In 1800, the Electoral College gave equal votes to Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. After much controversy, the U.S. House of Representatives elected Jefferson president, and the much-disappointed Burr, vice president. The next year, Joseph and seventeen-year-old Theodosia married in February, and during their honeymoon in Washington, D.C., attended her father’s inauguration.

Money did not buy the couple health nor Burr the political dynasty he craved. After the birth of her son—Aaron Burr Alston—Theodosia, already plagued by concern for her father, also suffered a series of illnesses. Aaron Burr had scandalized the nation by killing his political rival (and first secretary of the treasury) Alexander Hamilton, in a duel. Later, Burr was accused and acquitted of treason, and he left the country. While he was away, Joseph and Theodosia’s beloved only child—the child who was to redeem Burr’s name—was lost to malaria.

Alston had pursued a political career of his own, serving in the state legislature and then being elected governor of South Carolina. But the family again faced tragedy. In 1812, with British warships off the coast, an ailing Theodosia set sail to see her recently returned father. Her ship disappeared, reportedly lost in a storm. No word of Theodosia ever reached her grieving husband or her father, and her fate still fires the imagination. Alston’s career suffered with his involvement in Burr’s “conspiracy,” and after Theodosia’s death, he lost interest in life.

In 1816, at the age of thirty-nine, the man who had every advantage died alone in Charleston.

Hermia and Helena, oil on canvas, 1818, now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, was painted by Washington Allston, son of Brookgreen Plantation owner William Allston.

At the time of the American Revolution, Brookgreen was owned by William Allston. An avid supporter of the Patriot cause, Allston died without seeing the fledgling states become a new country. His widow, Rachel, married Dr. Henry Collins Flagg, a surgeon in the Continental army.

Among the most notable visitations at Brookgreen took place in 1791, when President George Washington, on his trip through the South, altered his itinerary to spend the night with the Flaggs. Years later, Flagg descendants died in the disastrous hurricane of 1893 that devastated the Carolina coast and sounded the death knell for rice cultivation in South Carolina.

Allston’s son, Washington, owned Springfield plantation. Named in honor of General George Washington, the heir would go on to become a renowned artist. As his interest in the arts grew, so did his desire to travel and study in Europe. In time, he sold the property in order to finance this travel. Washington Allston studied in London and Paris and became one of the leading Romantic artists in America.

In Paris, he met Washington Irving, author of the “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” and the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who wrote The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Samuel F. B. Morse, artist and inventor of the telegraph, was one of Allston’s art students. Allston died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was buried in Harvard Square.

Like Brookgreen, Springfield Plantation also had a Revolutionary connection. By 1742, Isaac Marion was planting rice there. Isaac’s brother was the Revolutionary partisan, Francis Marion, better known by his nickname, the “Swamp Fox.” The British never captured nor defeated Francis Marion as his raids disrupted British supply columns and Loyalist recruiting efforts.

By the late 1840s, both Brookgreen and Springfield plantations came under the ownership of Colonel Joshua John Ward. Ward, one of South Carolina’s most successful rice planters, had extensive holdings on the Waccamaw River. He also owned more than a thousand slaves, served as lieutenant governor of South Carolina, and developed an award-winning strain of large rice.

Laurel Hill Plantation, home to three generations of the Weston family, also was not immune to tragedy. The heirs of original immigrant Plowden Weston, a merchant turned rice planter, consolidated their holdings and social position so that by the mid-nineteenth century the estate was well established. In 1849, however, lightning struck the elegantly appointed new home of Francis Weston at Laurel Hill, and the resultant fire destroyed the house.

In 1859, Laurel Hill was sold to Daniel Jordan by Weston heir Plowden Charles Jennet Weston. But the outbreak of the Civil War made life along the Waccamaw increasingly uncertain. After Union gunboats sailed up the Waccamaw and federal troops visited the area, Jordan’s family abandoned the plantation and fled to Camden.

The Jordans never returned, and the plantation house fell into disrepair.

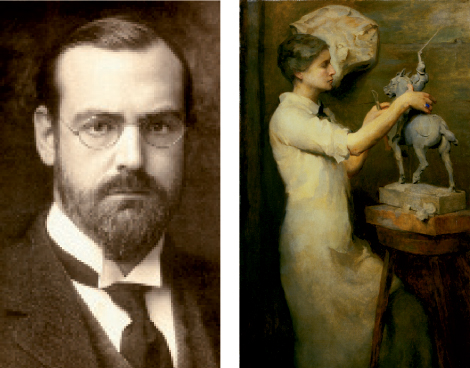

Archer and Anna Hyatt Huntington

By the early twentieth century, the once-mighty rice plantations of The Oaks, Brookgreen, Springfield, and Laurel Hill seemed to have reached the end of their glory days. The land had become hunting fields, as the once well-tended and meticulously maintained acreage became forgotten fields of wild rice, drawing flocks of waterfowl.

In 1920, the tide began to turn. Julius A. Mood, a Sumter physician whose daughter Julia Mood Peterkin is South Carolina’s only Pulitzer Prize winner, was among those who purchased part of the property that now encompasses the gardens. (Peterkin’s novel, Scarlet Sister Mary, won the Pulitzer Prize for literature in 1929.) In the intervening decade, the properties changed hands many times before Archer and Anna Huntington acquired the roughly 9,100 acres that stretch from the Atlantic to the Waccamaw.

Like so many of their predecessors on the sprawling tidal land, the Huntingtons were an unusual couple. Archer Milton Huntington (1870–1955) was born a Worsham. However, in 1884 his mother Arabella married Collis P. Huntington, founder of the Southern Pacific Railroad, and Huntington adopted him. Archer Huntington was a collector, author, poet, and philanthropist with a deep love and appreciation for Hispanic art and culture. Among his philanthropic ventures, Huntington established the Hispanic Society of America in 1904, donated land for the Museum of the American Indian (New York City) in 1915, and founded a new home for the American Numismatic Society in 1921.

Divorced from his first wife in 1918, he wed Anna Hyatt (1876–1973), the daughter of a Harvard paleontologist and widely exhibited sculptor, in March 1923. Hyatt’s father had encouraged his daughter’s art pursuits by erecting a studio in the family’s backyard.

The Hyatts traveled widely even while Anna battled tuberculosis for ten years. (King Alfonso XIII of Spain entertained the family before his abdication in 1931.) By age 24, Anna Hyatt was living in New York, supporting herself by selling her sculpture. She frequented zoos and circuses to sketch and model the animals. (At one time, the Huntingtons had at Haverstraw, their New York estate, a personal menagerie that included bears, wolves, and wild boars.) She continued to pursue her art almost until her death.

Throughout their lives, Archer and Anna Hyatt Huntington supported many museums and parks across the United States and abroad, including the Mariners’ Museum in Newport News, Virginia, and the Archer M. Huntington Art Gallery at the University of Texas at Austin. Following their purchase of the Brookgreen property in 1931 and the creation of the Archer M. and Anna Hyatt Huntington Sculpture Garden at Brookgreen, the Huntingtons spent part of each year here. They traveled south from their estates in New York and Connecticut by trailer. As Anna noted, the most comfortable mode of transport was a Greyhound bus modified to include living quarters.

Archer’s last visit was in 1945, Anna recalled, “because it was quite a journey.”

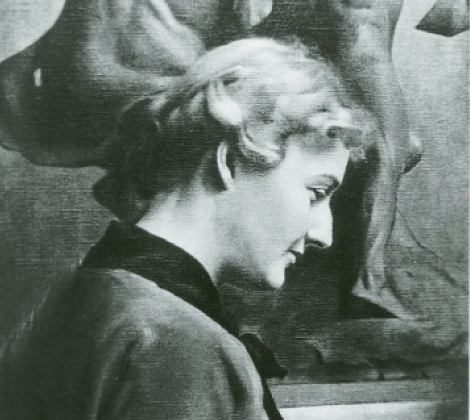

Anna Hyatt Huntington, who helped found Brookgreen Gardens with her husband, Archer, and moved here after his death, became one of the most prolific sculptors of the twentieth century.

Artist in Residence

Anna Vaughan Hyatt Huntington and her philanthropist husband, Archer, were in search of a place to escape the bitter New York winters, when they traveled to coastal South Carolina in the early 1920s. They stumbled upon the land at Brookgreen Gardens, with its sweeping views of the Atlantic and mild winter months, and they bought it, built a mansion, and fashioned an art studio for Anna, who was well on her way to becoming one of the foremost sculptors in America.

The spot was an ideal getaway, as they wrapped themselves in elaborate gardens that stretched as far as the eye could see. Before coming to South Carolina, Anna had studied with some of the leading artists in America: Her mentors included Hermon Atkins MacNeil and Gutzon Borglum, both of whom taught the budding sculptor while she attended the Art Students League of New York.

Through the years, Anna would become best known for her work on wild and domestic animal sculpture, as well as heroic monuments. Her sculpture was heavily influenced by her father’s early occupation as a palentologist at Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, as well as her mother’s illustrations of her father’s work.

The nation’s museums became her gallery, and the Grand Strand was her getaway, where she entertained other artists and family friends alike.

After her husband passed away in 1955, Anna continued to spend time at Brookgreen and sculpt until her own death in 1973. Today, her prolific work, showcased at Brookgreen Gardens, can be found across the country.

— Heidi Coryell Williams

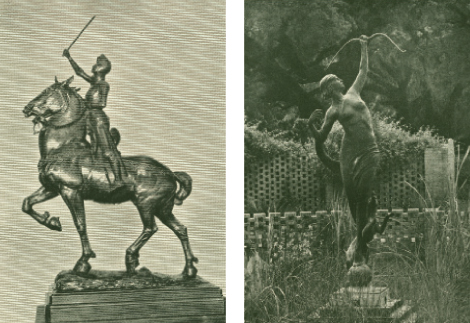

Joan of Arc and Diana of the Chase

Gallery Crawl

Look for Anna Hyatt Huntington’s notable works on display at museums across the nation

Their stories may differ, but the families of Brookgreen Gardens—Alstons, Allstons, Flaggs, Westons, and Huntingtons—all shared a common vision: to shape the natural landscape along the lumbering Waccamaw and make a life for themselves within those marshy confines.

Today, Brookgreen Gardens remains much more than a sculpture garden, arboretum, zoo, and art museum. The land itself serves as a palimpsest for the stories of Southern aristocracy—a manuscript of tales told and untold that will continue to be written and rewritten as time marches on.

Alexia Jones Helsley is an archivist, historian, and author. Retired from the S.C. Department of Archives and History, she currently teaches history at USC Aiken.

Plantation photographs, courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Columbia; Aaron Burr, courtesy of the Library of Congress; Theodosia Burr, courtesy of the South Caroliniana Library / painting courtesy, of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; Allston SELF-PORTRAIT, courtesy of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; Chimney photograph, courtesy of the S.C. Department of Archives and History/ Huntington photograph, courtesy of The Juley Collection, the Smithsonian American Art Museum; insets courtesy of the S.C. room collection, Greenville County library / Archer Huntington, courtesy of the Library of Congress Anna Hyatt Huntington, courtesy of the Mariners’ Museum